Milton J. Valencia and Patricia Wen Boston Globe

For live coverage of the trial, please click here.

When they retreat to the jury room Wednesday, the 12 people charged with determining Dzhokhar Tsarnaev’s sentence will not simply raise their hands to take a vote. They will embark on a meticulous process that could unfold over days, in which they wade through a complex checklist.

To show that they have weighed all the factors in the case, the jury will have to complete a lengthy form, marking their votes on the aggravating factors presented by the prosecution — such as whether the convicted Boston Marathon bomber deliberately targeted children — as well as the mitigating circumstances presented by defense attorneys, including the influence of his older brother, for each of the 17 death-penalty charges.

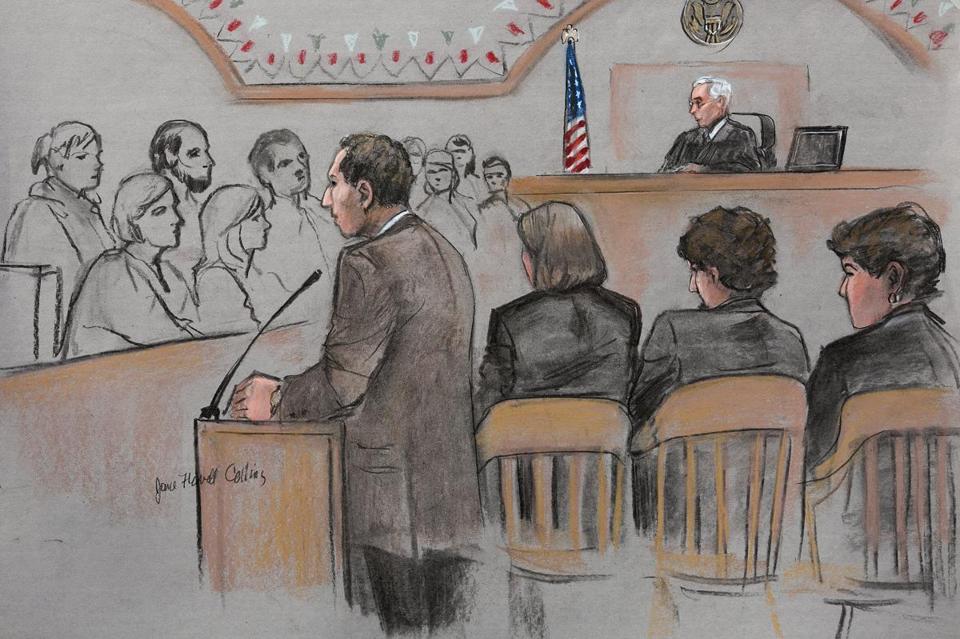

A courtroom sketch depicted prosecutor William Weinreb addressed the jury during closing arguments. Jane Flavell Collins/Reuters

Legal analysts say the thoroughness of the process is meant to assure that jurors focus on relevant factors and ignore prejudicial and arbitrary circumstances in determining a defendant’s fate.

“The jury has to consider the [evidence] that the government says is relevant, that justifies a death sentence, and then the jury makes a reasoned, morally responsible response to that evidence,” said George Kendall, a New York lawyer who has handled hundreds of death-penalty cases.

“The idea is we want to have a system of accountability.”

Unlike typical criminal cases, the jury that determined Tsarnaev’s guilt in the first phase of his trial is also tasked with deciding his punishment during this second phase of his trial.

And in deciding which sentence to bestow, the jurors will weigh the aggravating factors — or reasons Tsarnaev’s crimes were so heinous he deserves death — against the mitigating factors, or arguments that seek to explain and soften his culpability in the crimes.

The formula of arguing aggravating vs. mitigating factors in capital crimes was upheld by the US Supreme Court in 1976, in a case originating in Georgia, and it became the basis for modern federal death-penalty laws. The decision ended an unofficial moratorium on the death penalty that had begun four years earlier after the Supreme Court ruled that death-penalty laws were unconstitutional because they were being applied arbitrarily.

Under the modern application of the death penalty, jurors must consider aggravating factors and mitigating factors for each defendant, and they must record their conclusion on each of those factors on the verdict slip. They must then repeat the process for each count.

US District Judge George A. O’Toole Jr. has not released a copy of the verdict slip, but prosecutors have already identified aggravating factors in the case: that Tsarnaev intentionally sought to kill and inflict bodily injuries; that he targeted vulnerable victims, including children and spectators at the Marathon finish line; that he has shown no remorse; that the attacks were in the name of jihad, or terrorism; that one of his victims was a police officer; and that the attack was premeditated.

Jurors will have to be unanimous in finding that each of the aggravating factors was proved. They also must be unanimous if they choose to sentence Tsarnaev to death. A divided jury would result in a life sentence.

But jurors will also vote on the defense team’s mitigating factors, and they do not have to be unanimous on each one.

“The defense doesn’t have the same kind of burden; it’s the prosecutors who have the burden to prove this beyond a reasonable doubt, that death is the only appropriate sentence,” Kendall said.

Jurors will then weigh the totality of aggravating and mitigating factors before deciding on a sentence. O’Toole has already instructed jurors that choosing a sentence is not a matter of simple math of how many aggravating factors were proved vs. how many mitigating factors the defense presented, but a “reasoned, moral response” to the overall case.

“A single mitigating factor can outweigh several aggravating factors,” O’Toole told jurors.

The defense team has not publicly disclosed the mitigating factors it will list on the verdict sheet, but they will probably draw from the themes they have sought to crystallize in the trial: that Tsarnaev was an impressionable teenager who was manipulated by a dominating older brother; that brain science shows teenagers do not have a fully matured brain; that he came from a troubled upbringing, and was looking for guidance in a vulnerable time in his life; and that his family held to old cultural tradition that he obey the direction of his older brother.

Robert Sheketoff, a prominent Boston lawyer who represented admitted serial killer Gary Lee Sampson in a death-penalty trial more than a decade ago, said there is no formula for listing mitigating factors, and each case has its own characteristics. Although some factors will be routine for all cases — such as an argument that a defendant will still be punished if he or she is sentenced to life in prison — other factors could be more unique to a particular case.

“There’s no limit. As long as it’s a rational [argument], you can press it,” said Sheketoff. “If jurors take their oath seriously, they have to be thorough. And if they’re supposed to balance [the factors] and decide where the balance ends up, they’ve got to know what they will be balancing.”

Jurors sentenced Sampson to death — though the sentence was successfully appealed and he is awaiting a new trial — but jurors did find that several mitigating factors existed: that Sampson cooperated with authorities after his arrest; that he accepted responsibility for his crimes; and that people other than him would suffer grief or loss if he was sentenced to death.

Lawyers in other death-penalty cases have offered personal histories of the defendants as mitigation. Lawyers for Zacarias Moussaoui, who was convicted in connection with the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, cited racism he endured as a child, and his placement in orphanages as mitigating factors. Jurors could not reach a unanimous verdict and so spared his life after seven days of deliberations.

Lawyers for Kristen Gilbert, the nurse who killed patients in Western Massachusetts 15 years ago, argued that she was under “mental and emotional disturbance when the crimes were committed.”

Jurors added their own mitigating factor: that the “defendant’s sister will be adversely affected if she is executed.” Her life was spared after six hours of deliberations.

Kendall said jurors in Tsarnaev’s case will probably weigh each argument seriously, having sat through 27 days of testimony in both phases of the trial, and listening to more than 150 witnesses.

“It’s not just paperwork,” Kendall said. “It’s after all this evidence that the decision is being based on factors the law considers prudent and right ones.”

Jurors are scheduled to hear closing arguments Wednesday morning and could begin their deliberations that afternoon.