Eliza Griswold New York Times

There was something about Diyaa that his wife’s brothers didn’t like. He was a tyrant, they said, who, after 14 years of marriage, wouldn’t let their sister, Rana, 31, have her own mobile phone. He isolated her from friends and family, guarding her jealously. Although Diyaa and Rana were both from Qaraqosh, the largest Christian city in Iraq, they didn’t know each other before their families arranged their marriage. It hadn’t gone especially well. Rana was childless, and according to the brothers, Diyaa was cheap. The house he rented was dilapidated, not fit for their sister to live in.

Qaraqosh is on the Nineveh Plain, a 1,500-square-mile plot of contested land that lies between Iraq’s Kurdish north and its Arab south. Until last summer, this was a flourishing city of 50,000, in Iraq’s breadbasket. Wheat fields and chicken and cattle farms surrounded a town filled with coffee shops, bars, barbers, gyms and other trappings of modern life.

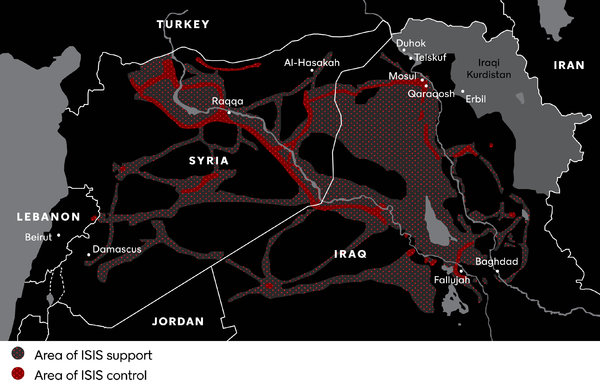

Then, last June, ISIS took Mosul, less than 20 miles west. The militants painted a red Arabic ‘‘n,’’ for Nasrane, a slur, on Christian homes. They took over the municipal water supply, which feeds much of the Nineveh Plain. Many residents who managed to escape fled to Qaraqosh, bringing with them tales of summary executions and mass beheadings. The people of Qaraqosh feared that ISIS would continue to extend the group’s self-styled caliphate, which now stretches from Turkey’s border with Syria to south of Fallujah in Iraq, an area roughly the size of Indiana.

In the weeks before advancing on Qaraqosh, ISIS cut the city’s water. As the wells dried up, some left and others talked about where they might go. In July, reports that ISIS was about to take Qaraqosh sent thousands fleeing, but ISIS didn’t arrive, and within a couple of days, most people returned. Diyaa refused to leave. He was sure ISIS wouldn’t take the town.

A week later, the Kurdish forces, known as the peshmerga, whom the Iraqi government had charged with defending Qaraqosh, retreated. (‘‘We didn’t have the weapons to stop them,’’ Jabbar Yawar, the secretary general of the peshmerga, said later.) The city was defenseless; the Kurds had not allowed the people of the Nineveh Plain to arm themselves and had rounded up their weapons months earlier. Tens of thousands jammed into cars and fled along the narrow highway leading to the relative safety of Erbil, the Kurdish capital of Northern Iraq, 50 miles away.

Piling 10 family members into a Toyota pickup, Rana’s brothers ran, too. From the road, they called Diyaa repeatedly, pleading with him to escape with Rana. ‘‘She can’t go,’’ Diyaa told one of Rana’s brothers, as the brother later recounted to me. ‘‘ISIS isn’t coming. This is all a lie.’’

The next morning Diyaa and Rana woke to a nearly empty town. Only 100 or so people remained in Qaraqosh, mostly those too poor, old or ill to travel. A few, like Diyaa, hadn’t taken the threat seriously. One man passed out drunk in his backyard and woke the next morning to ISIS taking the town.

As Diyaa and Rana hid in their basement, ISIS broke into stores and looted them. Over the next two weeks, militants rooted out most of the residents cowering in their homes, searching house to house. The armed men roamed Qaraqosh on foot and in pickups. They marked the walls of farms and businesses ‘‘Property of the Islamic State.’’ ISIS now held not just Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city, but also Ramadi and Fallujah. (During the Iraq War, the fighting in these three places accounted for 30 percent of U.S. casualties.) In Qaraqosh, as in Mosul, ISIS offered residents a choice: They could either convert or pay the jizya, the head tax levied against all ‘‘People of the Book’’: Christians, Zoroastrians and Jews. If they refused, they would be killed, raped or enslaved, their wealth taken as spoils of war.

No one came for Diyaa and Rana. ISIS hadn’t bothered to search inside their ramshackle house. Then, on the evening of Aug. 21, word spread that ISIS was willing to offer what they call ‘‘exile and hardship’’ to the last people in Qaraqosh. They would be cast out of their homes with nothing, but at least they would survive. A kindly local mullah was going door to door with the good news. Hoping to save Diyaa and Rana, their neighbors told him where they were hiding.

Diyaa and Rana readied themselves to leave. The last residents of Qaraqosh were to report the next morning to the local medical center, to receive ‘‘checkups’’ before being deported from the Islamic State. Everyone knew the checkups were really body searches to prevent residents from taking valuables out of Qaraqosh. Before ISIS let residents go — if they let them go — it was very likely they would steal everything they had, as residents heard they had done elsewhere.

Diyaa and Rana called their families to let them know what was happening. ‘‘Take nothing with you,’’ her brothers told Diyaa. But Diyaa, as usual, didn’t listen. He stuffed Rana’s clothes with money, gold, passports and their identity papers. Although she was terrified of being caught — she could be beheaded for taking goods from the Islamic State — Rana didn’t protest; she didn’t dare. According to her brothers, Diyaa could be violent. (Diyaa’s brother Nimrod disputed this, just as he does Diyaa’s alleged cheapness.)

At 7 the next morning, Diyaa and Rana made the five-minute walk from their home to Qaraqosh Medical Center Branch No. 2, a yellow building with red-and-green trim next to the city’s only mosque. As the crowd gathered, Diyaa phoned both his family and hers. ‘‘We’re standing in front of the medical center right now,’’ he said, as his brother-in-law recalled it. ‘‘There are buses and cars here. Thank God, they’re going to let us go.’’

It was a searing day. Temperatures reach as high as 110 degrees on the Nineveh Plain in summer. By 9 a.m., ISIS had separated men from women. Seated in the crowd, the local ISIS emir, Saeed Abbas, surveyed the female prisoners. His eyes lit on Aida Hana Noah, 43, who was holding her 3-year-old daughter, Christina. Noah said she felt his gaze and gripped Christina closer. For two weeks, she’d been at home with her daughter and her husband, Khadr Azzou Abada, 65. He was blind, and Aida decided that the journey north would be too hard for him. So she sent her 25-year-old son with her three other children, who ranged in age from 10 to 13, to safety. She thought Christina too young to be without her mother.

ISIS scanned the separate groups of men and women. ‘‘You’’ and ‘‘you,’’ they pointed. Some of the captives realized what ISIS was doing, survivors told me later, dividing the young and healthy from the older and weak. One, Talal Abdul Ghani, placed a final call to his family before the fighters confiscated his phone. He had been publicly whipped for refusing to convert to Islam, as his sisters, who fled from other towns, later recounted. ‘‘Let me talk to everybody,’’ he wept. ‘‘I don’t think they’re letting me go.’’ It was the last time they heard from him.

No one was sure where either bus was going. As the jihadists directed the weaker and older to the first of two buses, one 49-year-old woman, Sahar, protested that she’d been separated from her husband, Adel. Although he was 61, he was healthy and strong and had been held back. One fighter reassured her, saying, ‘‘These others will follow.’’ Sahar, Aida and her blind husband, Khadr, boarded the first bus. The driver, a man they didn’t know, walked down the aisle. Without a word, he took Christina from her mother’s arms. ‘‘Please, in the name of God, give her back,’’ Aida pleaded. The driver carried Christina into the medical center. Then he returned without the child. As the people in the bus prayed to leave town, Aida kept begging for Christina. Finally, the driver went inside again. He came back empty-handed.

Aida has told this story before with slight variations. As she, her husband and another witness recounted it to me, she was pleading for her daughter when the emir himself appeared, flanked by two fighters. He was holding Christina against his chest. Aida fought her way off the bus.

‘‘Please give me my daughter,’’ she said.

The emir cocked his head at his bodyguards.

‘‘Get on the bus before we kill you,’’ one said.

Christina reached for her mother.

‘‘Get on the bus before we slaughter your family,’’ he repeated.

As the bus rumbled north out of town, Aida sat crumpled in a seat next to her husband. Many of the 40-odd people on it began to weep. ‘‘We cried for Christina and ourselves,’’ Sahar said. The bus took a sharp right toward the Khazir River that marked an edge of the land ISIS had seized. Several minutes later, the driver stopped and ordered everyone off.

Led by a shepherd who had traveled this path with his flock, the sick and elderly descended and began to walk to the Khazir River. The journey took 12 hours.

The second bus — the one filled with the young and healthy — headed north, too. But instead of turning east, it turned west, toward Mosul. Among its captives was Diyaa. Rana wasn’t with him. She had been bundled into a third vehicle, a new four-wheel drive, along with an 18-year-old girl named Rita, who’d come to Qaraqosh to help her elderly father flee.

The women were driven to Mosul, where, the next day, Rana’s captor called her brothers. ‘‘If you come near her, I’ll blow the house up. I’m wearing a suicide vest,’’ he said. Then he passed the phone to Rana, who whispered, in Syriac, the story of what happened to her. Her brothers were afraid to ask any questions lest her answers make trouble for her. She said, ‘‘I’m taking care of a 3-year-old named Christina.’’

Syrian Christian refugees in Beirut, Lebanon, mourn the death of an elderly man, Benjamin Ishaya. He died of a head wound after being struck by a militant while fleeing his home village.CreditPeter van Agtmael/Magnum, for The New York Times

Most of Iraq’s Christians call themselves Assyrians, Chaldeans or Syriac, different names for a common ethnicity rooted in the Mesopotamian kingdoms that flourished between the Tigris and the Euphrates Rivers thousands of years before Jesus. Christianity arrived during the first century, according to Eusebius, an early church historian who claimed to have translated letters between Jesus and a Mesopotamian king. Tradition holds that Thomas, one of the Twelve Apostles, sent Thaddeus, an early Jewish convert, to Mesopotamia to preach the Gospel.

As Christianity grew, it coexisted alongside older traditions — Judaism, Zoroastrianism and the monotheism of the Druze, Yazidis and Mandeans, among others — all of which survive in the region, though in vastly diminished form. From Greece to Egypt, this was the eastern half of Christendom, a fractious community divided by doctrinal differences that persist today: various Catholic churches (those who look to Rome for guidance, and those who don’t); the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox (those who believe Jesus has two natures, human and divine, and those who believe he was solely divine); and the Assyrian Church of the East, which is neither Catholic nor Orthodox.

When the first Islamic armies arrived from the Arabian Peninsula during the seventh century, the Assyrian Church of the East was sending missionaries to China, India and Mongolia. The shift from Christianity to Islam happened gradually. Much as the worship of Eastern cults largely gave way to Christianity, Christianity gave way to Islam. Under Islamic rule, Eastern Christians lived as protected people, dhimmi: They were subservient and had to pay the jizya, but were often allowed to observe practices forbidden by Islam, including eating pork and drinking alcohol. Muslim rulers tended to be more tolerant of minorities than their Christian counterparts, and for 1,500 years, different religions thrived side by side.

One hundred years ago, the fall of the Ottoman Empire and World War I ushered in the greatest period of violence against Christians in the region. The genocide waged by the Young Turks in the name of nationalism, not religion, left at least two million Armenians, Assyrians and Greeks dead. Nearly all were Christian. Among those who survived, many of the better educated left for the West. Others settled in Iraq and Syria, where they were protected by the military dictators who courted these often economically powerful minorities.

From 1910 to 2010, the percentage of the Middle Eastern population that was Christian — in countries like Egypt, Israel, Palestine and Jordan — continued to decline; once 14 percent of the population, Christians now make up roughly 4 percent. (In Iran and Turkey, they’re all but gone.) In Lebanon, the only country in the region where Christians hold significant political power, their numbers have shrunk over the past century, to 34 percent from 78 percent of the population. Low birthrates have contributed to this decline, as well as hostile political environments and economic crisis. Fear is also a driver. The rise of extremist groups, as well as the perception that their communities are vanishing, causes people to leave.

For more than a decade, extremists have targeted Christians and other minorities, who often serve as stand-ins for the West. This was especially true in Iraq after the U.S. invasion, which caused hundreds of thousands to flee. ‘‘Since 2003, we’ve lost priests, bishops and more than 60 churches were bombed,’’ Bashar Warda, the Chaldean Catholic archbishop of Erbil, said. With the fall of Saddam Hussein, Christians began to leave Iraq in large numbers, and the population shrank to less than 500,000 today from as many as 1.5 million in 2003.

The Arab Spring only made things worse. As dictators like Mubarak in Egypt and Qaddafi in Libya were toppled, their longstanding protection of minorities also ended. Now, ISIS is looking to eradicate Christians and other minorities altogether. The group twists the early history of Christians in the region — their subjugation by the sword — to legitimize its millenarian enterprise. Recently, ISIS posted videos delineating the second-class status of Christians in the caliphate. Those unwilling to pay the jizya tax or to convert would be destroyed, the narrator warned, as the videos culminated in the now-infamous scenes of Egyptian and Ethiopian Christians in Libya being marched onto the beach and beheaded, their blood running into the surf.

The future of Christianity in the region of its birth is now uncertain. ‘‘How much longer can we flee before we and other minorities become a story in a history book?’’ says Nuri Kino, a journalist and founder of the advocacy group Demand for Action. According to a Pew study, Christians face religious persecution in more countries than any other religious group. ‘‘ISIL has put a spotlight on the issue,’’ says Anna Eshoo, a California Democrat in the U.S. House of Representatives, whose parents are from the region and who advocates on behalf of Eastern Christians. ‘‘Christianity is under an existential threat.’’

One of the main pipelines for Christians fleeing the Middle East runs through Lebanon. This spring, thousands of Christians from villages in northeastern Syria along the Khabur River found shelter in Lebanon as they fled an ISIS assault in which 230 people were seized for ransom. This wasn’t the first time that members of this tight-knit community had been driven from their homes. Many of these villagers were descendants of those who, in 1933, fled Iraq after a massacre of Assyrian Christians left 3,000 dead in one day.

On a recent Saturday, 50 of these refugees gathered for a funeral at the Assyrian Church of the East in Beirut, which sits on the steep slope of Mount Lebanon, not far from a BMW-Mini Cooper dealership and a Miss Virgin Jeans shop. The priest, the Rev. Sargon Zoumaya, buttoned his black cassock over a blue clerical shirt as he prepared to officiate over the burial of Benjamin Ishaya, who arrived just months before, displaced from one of the villages ISIS attacked. (He had died of complications following a head wound inflicted by a jihadist.)

‘We’re afraid our whole society will vanish,’’ said Zoumaya, who left his Khabur River village more than a decade ago to study in Lebanon. He picked up his prayer book and headed downstairs to the parish house. The church was helping to care for 1,500 Syrian families. ‘‘It’s too much pressure on us, more than we can handle,’’ he said. The families didn’t want to live in the notoriously overcrowded Lebanese refugee camps that had filled with one-and-a-half million Syrians fleeing the civil war. They no longer wanted to live among Muslims. Instead they crammed into apartments with exorbitant rents that the church subsidized as best it could.

The headquarters of a Dwekh Nawsha Assyrian Christian militia unit near the front line against ISIS in Baqofa, Iraq. CreditPeter van Agtmael/Magnum, for The New York Times

Inside the church, men and women sat in two separate circles. A young woman passed out Turkish coffee in paper cups. Waves of keening rose from the ring of women, led by Ishaya’s widow. Wearing an olive green suit, she sat at the head of the open coffin, weeping, as women touched her husband’s body. Nearby, her son, Bassam Ishaya, nursed two broken feet. He’d been trying to support his family by repairing couches until one dropped on him. The Ishaya family left Syria with nothing. ISIS, Bassam said, told them they ‘‘either had to pay the jizya, convert or be killed.’’ He pointed to a blue crucifix tattoo on his right arm. ‘‘Because of this, I had to wear long sleeves,’’ he said.

To escape, the Ishayas were airlifted from Al-Hasakah, a town in northeastern Syria, which had been under the joint control of the Assad government and the Kurds but has since largely fallen to ISIS, and flown 400 miles to Damascus. From there, they drove to the Lebanese border. Syrian Air charged $180 for the flights; Assad’s government charged $50 a person, the refugees at the funeral said.

Since the civil war broke out in Syria in 2011, Assad has allowed Christians to leave the country. Nearly a third of Syria’s Christians, about 600,000, have found themselves with no choice but to flee the country, driven out by extremist groups like the Nusra Front and now ISIS.

‘‘As president, he made the sheep and the wolf walk together,’’ Bassam said. ‘‘We don’t care if he stays or goes, we just want security.’’ Assad has used the rise of ISIS to solidify his own support among those who remain, sowing the same fear among them that he tries to spread in the West: that he is the only thing standing in the way of an ISIS takeover. This argument has been largely effective. As Samy Gemayel, leader of the Kataeb party in Lebanon, said: ‘‘When Christians saw Christians being beheaded, those who saw Assad as the enemy chose the lesser of two evils. Assad was the diet version of ISIS.’’

Like most of the refugees in the parish house, Bassam wasn’t planning on returning to Syria. He was searching for a way to the West. His brother Yussef moved to Chicago two years earlier. He didn’t have a job yet, but his wife worked at Walmart. Maybe they would help. He wanted to leave like everyone else, although it would hasten the end of Christianity in Syria. No one would go home after what ISIS had done. ‘‘Christians will all leave,’’ he said. ‘‘What can I do? I have four kids, I can’t leave them here to die.’’

After his father’s coffin was sealed, Bassam and the rest of the male mourners filed out. As the women looked on, the men filled waiting cars and drove, past a cement factory, to a nearby graveyard. Zoumaya swung a censer of frankincense along the narrow pathway. But neither the smoke nor the wilting rose bushes could mask the reek of corpses. Behind the priest, Bassam hobbled on crutches. The mourners lifted the coffin into a wall of doors, which resembled the shelving units in a morgue. This was a pauper’s grave. Since the family couldn’t afford the fee, the church paid $500 to place the coffin here. In a few months, the body would be quietly burned, although cremation is anathema to Eastern Christian doctrine. The ashes would take up less space in this overcrowded city of the dead.

‘‘We ran from the war only to die in the street,’’ one mourner said.

Later, Zoumaya talked of his family members, who were among the 230 captured by ISIS. At noon, on the day ISIS arrived in his wife’s village, Zoumaya called his father-in-law to check in.

‘‘This is ISIS,’’ said the man who answered.

‘‘Please let my family go,’’ the priest begged. ‘‘They’ve done nothing to you. They’re not fighting.’’

‘‘These people belong to us now,’’ the man said. ‘‘Who is this calling?’’

Zoumaya hung up. He feared what ISIS might do if they knew who he was. But this was not the end of his communication with them; they sent him photographs via WhatsApp. He pulled out his phone to show them. Here was a jihadi on a motorcycle, grinning in front of the charred grocery store that belonged to his father. Here was a photo, before ISIS arrived, of a 3-month-old’s baptism. Here was a snapshot of the family dressed up for Somikka, Assyrian Halloween, during which adults don frightening costumes to scare children into fasting for Lent.

‘‘All these people are missing,’’ he said.

ISIS wants $23 million for these captives, $100,000 each, a sum no one can pay.

This spring the U.N. Security Council met to discuss the plight of Iraq’s religious minorities. ‘‘If we attend to minority rights only after slaughter has begun, then we have already failed,’’ Zeid Ra’ad al-Hussein, the high commissioner for Human Rights, said. After the conference ended, there was mounting anger at American inaction. Although the airstrikes were effective, since October 2013, the United States has given just $416 million in humanitarian aid, which falls far short of what is needed. ‘‘Americans and the West were telling us they came to bring democracy, freedom and prosperity,’’ Louis Sako, the Chaldean Catholic Patriarch of Babylon who addressed the Security Council, wrote to me in a recent email. ‘‘What we are living is anarchy, war, death and the plight of three million refugees.’’

Of the 3.1 million displaced Iraqis, 85 percent are Sunnis. No one has suffered more at the hands of ISIS than fellow Muslims. Other religious minorities have been affected as well and in large numbers: the Yazidis, who were trapped on Mount Sinjar in Northern Iraq last summer, as ISIS threatened them with genocide; as well as Shia Turkmen; Shabak; Kaka’i; and the Mandeans, who follow John the Baptist. ‘‘Everyone has seen the forced conversions, crucifixions and beheadings,’’ David Saperstein, the United States ambassador at large for religious freedom, said. ‘‘To see these communities, primarily Christians, but also the Yazidis and others, persecuted in such large numbers is deeply alarming.’’

It has been nearly impossible for two U.S. presidents — Bush, a conservative evangelical; and Obama, a progressive liberal — to address the plight of Christians explicitly for fear of appearing to play into the crusader and ‘‘clash of civilizations’’ narratives the West is accused of embracing. In 2007, when Al Qaeda was kidnapping and killing priests in Mosul, Nina Shea, who was then a U.S. commissioner for religious freedom, says she approached the secretary of state at the time, Condoleezza Rice, who told her the United States didn’t intervene in ‘‘sectarian’’ issues. Rice now says that protecting religious freedom in Iraq was a priority both for her and for the Bush administration. But the targeted violence and mass Christian exodus remained unaddressed. ‘‘One of the blind spots of the Bush administration was the inability to grapple with this as a direct byproduct of the invasion,’’ says Timothy Shah, the associate director of Georgetown University’s Religious Freedom Project.

More recently, the White House has been criticized for eschewing the term ‘‘Christian’’ altogether. The issue of Christian persecution is politically charged; the Christian right has long used the idea that Christianity is imperiled to rally its base. When ISIS massacred Egyptian Copts in Libya this winter, the State Department came under fire for referring to the victims merely as ‘‘Egyptian citizens.’’ Daniel Philpott, a professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame, says, ‘‘When ISIS is no longer said to have religious motivations nor the minorities it attacks to have religious identities, the Obama administration’s caution about religion becomes excessive.’’

Last fall, Obama did refer to Christians and other religious minorities by name in a speech, saying, ‘‘we cannot allow these communities to be driven from their ancient homelands.’’ When ISIS threatened to eradicate the Yazidis, ‘‘it was the United States that stepped in to beat back the militants,’’ Alistair Baskey, a spokesman for the National Security Council, says. In northeastern Syria, where ISIS is still launching attacks against Assyrian Christian villages, the U.S. military recently come to their aid, Baskey added. Refugees are a thornier issue. Of the more than 122,000 Iraqi refugees admitted to the United States, nearly 40 percent already belong to oppressed minorities. Admitting more would be difficult. ‘‘There are limits to what the international community can do,’’ Saperstein said.

Eshoo, the Democratic congresswoman, is working to establish priority refugee status for minorities who want to leave Iraq. ‘‘It’s a hair ball,’’ she says. ‘‘The average time for admittance to the United States is more than 16 months, and that’s too long. Many will die.’’ But it can be difficult to rally widespread support. The Middle East’s Christians often favor Palestine over Israel. And because support of Israel is central to the Christian Right — Israel must be occupied by the Jews before Jesus can return — this stance distances Eastern Christians from a powerful lobby that might otherwise champion their cause. Recently, Ted Cruz admonished an audience of Middle Eastern Christians at an In Defense of Christians event in Washington, telling them that Christians ‘‘have no better ally than the Jewish state.’’ Cruz was booed.

The fate of Christians in the Middle East isn’t simply a matter of religion; it is also integral to what kinds of societies will flourish as the region’s map fractures. In Lebanon, for example, where Christians have always played a powerful role in government, they increasingly serve as a buffer between Sunni and Shia. For nearly 70 years, Lebanon was a proxy battleground for the conflict between Israel and Palestine. Across the region, that conflict is now secondary to the shifting tectonic plates of the Sunni-Shia divide, which threatens terrible bloodshed.

Earlier this year, Lebanon closed its borders to almost everyone escaping the war in Syria but made an exception for Christians fleeing ISIS. When the extremists attacked the villages along the Khabur River, the interior minister, Nouhad Machnouk, ordered the official in charge of the border to allow Christians to enter the country. ‘‘I can’t put this in writing,’’ the border official said. Machnouk replied, ‘‘O.K., say it aloud, word by word.’’

Machnouk told me this story on a recent evening. ‘‘They’re paying much, much, much more than others,’’ in both Syria and Iraq, he said. ‘‘They’re not Sunni and not Shia, but they’re paying more than both.’’ We sat in his airy office, housed in a former art school from the Ottoman era. It was decorated with his private collection of Greek and Roman antiquities, including a carved basalt head with finely wrought curls. For the minister, a moderate Sunni, sheltering Christians is as much a sociopolitical imperative as a moral one.

In Lebanon, the tension between Sunni and Shia plays out in a system of political patronage, which has split the Christian community into two rival political parties, both born of the country’s 15-year-long civil war. The pro-Saudi Future movement, which consists of mainly Sunnis, supports the Christian leader Samir Geagea, who lives atop Mount Lebanon behind three check points, two X-ray machines and a set of steel doors. Hezbollah, which is Shia and backed by Iran, has been openly allied since 2006 with the Free Patriotic Movement (F.P.M.), a Christian Party headed by Michel Aoun. For Hezbollah, Christians offer an opportunity to forge an alliance with a fellow minority. (Of the world’s one and a half billion Muslims, only 10 to 20 percent are Shia.)

‘‘It’s a political game,’’ Alain Aoun, a member of Parliament for the F.P.M. and Michel Aoun’s nephew, told me. The emergence of ISIS has strengthened the alliance. ‘‘The Christians are happy to have anyone who can fight against I.S.’’ Hezbollah has paid young Christian men from Lebanon’s impoverished Bekaa Valley a one-time $500 to $2,000 fee to fight ISIS.

‘‘Christians here are making the same calculation that Obama does,’’ Hanin Ghaddar, the managing editor of NOW, a news website in Lebanon, said, referring to Obama’s willingness to support Iran as a bulwark against Sunni extremism. For many Christians in the Middle East, a Shia alliance offers a hope of survival, however slim. Ghaddar, an independent Shia, says that it is uncertain how these tenuous allegiances will play out. This spring, pro-Iranian forces of Hezbollah were battling Sunni extremists in Syria. No one knew who would prevail. ‘‘It’s like ‘Game of Thrones,’ ’’ she said. ‘‘We’re waiting for the snow to melt.’’

A bullet wound on the arm of Raed Sabah Matt, a former member of the Iraqi Army who survived an attack by Al Qaeda in Mosul and is now a member of an anti-ISIS Christian militia.CreditPeter van Agtmael/Magnum, for The New York Times

The front line against ISIS in Northern Iraq is marked by an earthen berm that runs for hundreds of miles over the Nineveh Plain. A string of Christian towns now stands empty, and the Kurdish forces occupy what, for thousands of years, was Assyrian, Chaldean and Syriac land. In one, Telskuf, seized by ISIS last year, the main square is overgrown with brambles and thistles. It was once a thriving market town. Every Thursday, hundreds came to buy clothes, honey and vegetables. Telskuf was home to 7,000 people; now only three remain.

The Nineveh Plain Forces, a 500-member Assyrian Christian militia, patrols the town. The N.P.F. is one of five Assyrian militias formed during the past year after the rout of ISIS. It shares a double aim with two other militias, Dwekh Nawsha, an all-volunteer force of around 100, and the Nineveh Plains Protection Units, a battalion of more than 300: to help liberate Christian lands from ISIS and to protect their people, possibly as part of a nascent national guard, when they return home. The two other militias are the Syriac Military Council, which is fighting alongside the Kurds in northeastern Syria, and the Babylonian Brigades, which operate under Iraq’s Shia-dominated militias.

A few of these militias are aided by a handful of American, Canadian and British citizens, who, frustrated with their governments’ lack of response to ISIS, have traveled to Syria and Iraq to fight on their own. Some come in the name of fellow Christians. Some come to relive their roles in the United States invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan — or to make amends for them. One American named Matthew VanDyke, the founder of Sons of Liberty International, a security company, has provided free training for the N.P.U. and is now about to work with a second militia, Dwekh Nawsha. VanDyke, who is 36, traveled to Libya in 2011 to fight against Muammar el-Qaddafi’s forces; he was captured and spent 166 days in solitary confinement before escaping and returning to combat. He has no formal military training, but since last fall, he has brought American veterans to Iraq to help the N.P.U., including James Halterman, a veteran of Afghanistan and Iraq, who found the group on the Internet after watching a segment about Westerners fighting ISIS on Fox News. The United States government does not support groups like VanDyke’s. ‘‘Americans who have traveled to Iraq to fight are not part of U.S. efforts in the region,’’ Joseph Pennington, the consul general in Erbil, says. ‘‘We wish they would not come here.’’

In Iraq, the militias operate at the front only with the approval of the Kurdish peshmerga, who are using the fight against ISIS to expand their territory into the Nineveh Plain, long a disputed territory between Arabs and Kurds. Even to travel 1,000 yards between bases and forward posts, the Christian militias must ask the Kurds for permission. The Kurds are looking to integrate all the Christian militias into their force; they have succeeded with the N.P.F. and two others. But the N.P.U. remains wary. They fear that the Kurds are using the Christian cause to seize territory for a greater Kurdistan. And because the Kurdish forces abandoned them as ISIS approached, the militias want the right to protect their own people. For now, they make do with the help they can find. Romeo Hakari, the head of the N.P.F., said, ‘‘We want U.S. trainers, but we can’t even afford to buy weapons.’’ After his militia purchased 20 AK-47s in an open market in Erbil, the Kurds gave them 100 more.

Other than a daily mortar or two launched by ISIS from a village a mile and a half away, the area the N.P.U. patrolled was a sleepy target. After coalition airstrikes pushed ISIS out of Telskuf last summer, the group retreated about a mile and a half to the southwest. Beyond a bulldozed trench and a line of burlap sandbags littered with sunflower-seed shells, 12 black flags fluttered over a village. Three weeks earlier, at 4:20 a.m., two suicide bombers carrying a ladder to place over the trench attacked this forward post. The suicide attack was foiled after the U.S.-led coalition against ISIS launched airstrikes, which killed 13 ISIS fighters, Manaf Yussef, a Kurdish security official in charge of this front, said. ‘‘Without airstrikes, we’d lose,’’ he said. Minutes later, a high whistle signaled an incoming ISIS shell, which set fire to a nearby wheat field. The land is sere due to a drought.

As a column of smoke from the daily ISIS shell billowed into the blue sky, five Assyrian fighters belonging to the Nineveh Plain Forces went from house to house to evacuate the last residents of Telskuf — three old women. When the N.P.F. commander, Safaa Khamro, pushed open the door of the first house, Christina Jibbo Kakhosh began to cry. She was 91.

‘‘I have no running water,’’ she said. Less than four feet tall, she peered up at Khamro through bottle-thick glasses.

‘‘I fixed it for you yesterday,’’ Khamro said.

A member of a Christian militia unit tries to persuade Kamala Karim Shaya, one of the last residents of Telskuf, to move to a secured home near their barracks. Credit Peter van Agtmael/Magnum, for The New York Times

‘‘I forgot,’’ she said. She shuffled back inside and beckoned him to follow. Her refrigerator was flung open; because there was no electricity, it served as a pantry. A half-eaten jar of tahini, a lighter and a pair of scissors sat on a table in front of the mattress on which she slept. When she heard her visitors were American, she said: ‘‘Three of my children are in America. Only one has called me.’’

Khamro tried to persuade her to come to a house near the base where she would be safer. ‘‘It has satellite TV,’’ he said. She packed a small satchel and left with the patrol. ‘‘That’s my uncle’s house,’’ one Assyrian fighter said as he passed a padlocked gate. ‘‘He’s in Australia now.’’ The patrol passed St. Jacob’s Church, where ISIS fighters had destroyed a porcelain statue of Jesus, which was now missing its face. An icon of a martyr having his fingers cut off by Tamerlane, who massacred tens of thousands of Assyrian Christians during the 14th century, hung on the wall.

Nearby, the N.P.F. had replaced the cross that ISIS fighters filmed themselves hurling down. Khamro was a politician in Telskuf before ISIS invaded. He owned one of the 480 now-shuttered shops, a boutique that sold women’s and children’s clothes. He’d sent his wife and children to Al Qosh, 10 miles to the north, a safer Christian city.

Khamro turned off the main drag and into a warren of overgrown pathways. He stopped before a chicken-wire awning, calling out ‘‘Auntie’’ to Kamala Karim Shaya, who sat on her front stoop, a kerchief tied over her thick white ponytail. When she learned that Khamro had come to move her out of her clay home, she began to scream: ‘‘Even if my father stands up in his grave, I will not leave this house. No, no, no, no, no, never, never, never,’’ she shouted. Khamro, who refused to move her by force, had no choice but to pass on.

Even if ISIS is defeated, the fate of religious minorities in Syria and Iraq remains bleak. Unless minorities are given some measure of security, those who can leave are likely to do so. Nina Shea of the Hudson Institute, a conservative policy center, says that the situation has grown so dire that Iraqi Christians must either be allowed full residency in Kurdistan, including the right to work, or helped to leave. Others argue that it is essential that minorities have their own autonomous region. Exile is a death knell for these communities, activists say. ‘‘We’ve been here as an ethnicity for 6,000 years and as Christians for 1,700 years,’’ says Dr. Srood Maqdasy, a member of the Kurdish Parliament. ‘‘We have our own culture, language and tradition. If we live within other communities, all of this will be dissolved within two generations.’’

The practical solution, according to many Assyrian Christians, is to establish a safe haven on the Nineveh Plain. ‘‘If the West could take in so many refugees and the U.N.H.C.R. handle an operation like that, then we wouldn’t ask for a permanent solution,’’ says Nuri Kino, of A Demand for Action. ‘‘But the most realistic option is returning home.’’

‘‘We don’t have time to wait for solutions,’’ said the Rev. Emanuel Youkhana, the head of Christian Aid Program Northern Iraq. ‘‘For the first time in 2,000 years, there are no church services in Mosul. The West comes up with one solution by granting visas to a few hundred people. What about a few hundred thousand?’’ If Iraq devolves into three regions — Sunnis, Shia and Kurds — there could be a fourth for minorities. ‘‘Iraq is a forced marriage between Sunni, Shia, Kurds and Christians, and it failed,’’ Youkhana said. ‘‘Even I, as a priest, favor divorce.’’

Proponents say a safe haven wouldn’t require an international force or a no-fly zone, neither of which is likely to find much support in the United States or among its allies. U.S. policy does play a role. When Congress was asked to approve $1.6 billion in aid for Iraqi forces fighting ISIS — the Iraqi Army, the Kurds and the Sunni tribes — it amended the bill to explicitly include local forces on the Nineveh Plain, but also passed legislation directing the State Department to implement a safe haven there. Ultimately, however, the responsibility lies with the Iraqis. Pennington, the consul general, said, ‘‘The creation of a safe haven in the Nineveh Province would be an idea for the Iraqi Parliament in accordance with the Iraqi Constitution.’’

Tarek Mitri, a former Lebanese minister and a former special representative to the U.N. secretary general for Libya, says that his impression in speaking to officials in the White House ‘‘is that Obama is in a withdrawal mood. He thinks that he was elected to withdraw from Afghanistan and Iraq and to make a deal with Iran. If this is the mood, then we shouldn’t expect much or ask much from the Americans.’’ Baskey, of the National Security Council, counters that ‘‘rather than withdrawing, the president and this administration have, in fact, remained deeply engaged, building and leading a coalition of some 60 nations to degrade and ultimately destroy ISIL.’’

The last time Rana, one of the women taken by ISIS from Qaraqosh, was able to speak to her family by phone was in September. She told them what had befallen Rita and Christina. Rita had been given as a slave to a powerful member of ISIS; Christina was given to a family to be raised as a Muslim.

Rana said little about her own circumstances, and her family didn’t ask. To be honest, they weren’t sure they wanted to know what ISIS had done to her.

For months now, the phone Rana used has been switched off. ‘‘There’s word they’re still alive,’’ Rabee Mano, 36, a refugee from Qaraqosh who runs an underground railroad out of the Islamic State, told me one recent evening over beer and kebabs. ‘‘She’s been ‘married’ to a powerful guy in ISIS,’’ he added, as he sat in the garden at the Social Academic Center in Ankawa, a Christian suburb of Erbil. At the next table, three gleeful men poured straight vodka into plastic cups. Over the past year, Ankawa has swelled by 60,000 as refugees have poured in.

For nearly a year, Mano has been trying to buy freedom for Rana, Rita and Christina from ISIS. Through his network of contacts, a greedy ISIS member, friends in Arab villages and a brave taxi driver, Mano has paid to free 45 people. The haggling is made easier by the fact that ISIS members frequently trade women among themselves, so the buying and selling of people doesn’t raise suspicion. This work has cost him $10,000, which he raised by opening a carwash. He sent $800 to a member of ISIS, saying he would send more when the women and the child made it to safety. But the man had done nothing of what he promised.

Before Mano fled his hometown last August, he dealt in commercial real estate. ‘‘You can see my buildings from Google Earth,’’ he said. At the picnic table, he pulled an expired Arizona driver’s license from his wallet.It was a temporary license from 2011, the year he came to the United States and tried to buy 48 apartments. The deal fell through, so he went home; now his passport had expired. He lost about $1.5 million, he said.

He longed to return to the Nineveh Plain. ‘‘Even though all of my money is in the garbage, I’ll be O.K. if we get this safe haven,’’ he said. ‘‘If it takes too long, we’ll be annihilated.’’ It was all he thought about. ‘‘Are we going home or not?’’ he asked. ‘‘This safe haven is the last chance we have, or Christianity will be finished in Iraq.’’

Earlier, a text message came in from Mosul. One of his contacts was having trouble locating a woman named Nabila, who was ready to be smuggled to safety. Mano had instructed her to hang a black cloth in her window so that her rescuer could find the right house. But the wind had blown the cloth to the ground, and now her would-be rescuer couldn’t tell where she was being held. They would have to try again. ‘‘I’ll tell her to hang a blanket,’’ Mano said. They would find her, he hoped, if the blanket held its weight against the wind.

Correction: August 9, 2015 An article on July 26 about Christianity in the Middle East misstated a statistic regarding the Christian population in the region. It was the percentage of the overall population that is Christian that declined between 1910 and 2010, not the total number of Christians.

Correction: August 30, 2015 An article on July 26 about Christianity in the Middle East described incorrectly a finding in a Pew study about religious hostilities. The study reported that Christians face religious persecution in more countries than any other religious group; it did not say that more Christians face religious persecution than at anytime since their early history.

Eliza Griswold is the author of ‘‘The Tenth Parallel: Dispatches From the Fault Line Between Christianity and Islam.’’