Sean Kirst Syracuse.com

In the Jewish calendar, Chavie Zelmanowitz said, the night before is the same as the next day. It is fitting, then, that when she closes her eyes and thinks of her brother-in-law, Abe Zelmanowitz, she sees him on the evening of September 10, 2001, dripping wet, at the door.

Chavie Zelmanowitz, center, with a photo of her brother-in-law Abe and members of the Burke family, in 2011, at one of the memorial pools, built on the footprints of the twin towers in memory of the September 11 attacks in New York City: Abe Zelmanowitz and Capt. Billy Burke were together with Abe’s friend Ed Beyea, a paraplegic man in a wheelchair, when the towers fell on September 11, 2001. (Chavie Zelmanowitz | Submitted image)

Usually, Abe carried an umbrella when he left their Brooklyn home. He forgot it that night, when he went to the synagogue for evening prayers in memory of his grandfather. On his way back, a hard rain fell on New York. Abe, soaked, walked into the house.

“My last vivid memory of him,” Chavie said, “is the two of us standing there, laughing.”

Abe changed into dry clothes and settled in for Monday night football. At 55, he’d often watch television with his brother, Chavie’s husband Jack: Maybe it’d be sports. Maybe it’d be ‘The Sopranos,’ on HBO. Abe fell asleep so often by the TV that it became a family joke: Chavie would wake him and say, “Get up. It’s time to go to bed.”

As for the drenched shirt and pants, Abe was considerate, as always. He hung them to dry, on a pipe in the laundry room.

It was a long time before Chavie allowed herself to take them down.

Abe worked in the north tower of the World Trade Center. He was there on September 11, 2001, when terrorist hijackers turned crowded jetliners into missiles in Manhattan and Washington D.C., when almost 3,000 people died in those attacks.

Chavie’s brother-in-law, this unassuming bachelor who’d lived quietly for years with his brother and sister-in-law, had a chance to leave the towers, to save his own life.

He turned it down.

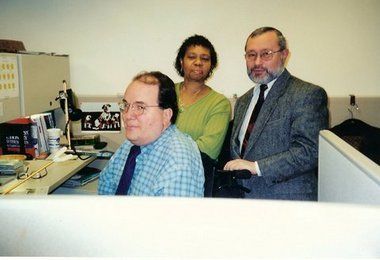

Abe worked as a computer analyst with Blue Cross. A colleague, Ed Beyea, was a close friend. He and Abe appreciated music of all varieties, Chavie said: The Beatles. Opera. Classical. They had great range. After work, they’d play computer games of golf or chess.

Ed Beyea, Beyea’s aide Erma Fuller, and Abe Zelmanowitz: Zelmanowitz told Fuller to leave the north tower on September 11, 2001, believing he and Beyea would be down shortly. Chavie Zelmanowitz | Submitted image

“Ed had a very distinguished voice, a voice that really made a statement, and I’d always know it was him when he would call,” Chavie said. The two men enjoyed sharing a meal. Ed, a paraplegic, used a wheelchair. Whenever Ed’s condition put him in the hospital, Abe – on the way home from work – would stop by to visit.

On September 11, as thousands evacuated the burning towers, Abe Zelmanowitz wasn’t ready to go down. Ed was a big man, in a heavy wheelchair. The elevators were uncertain, at best. There seemed to be no way, at that moment, for Ed to leave the 27th floor.

His friend wasn’t leaving without him.

“People who knew (Abe) throughout his life: They’ll tell you this final act was the way he always was,” Chavie said.

She said Abe asked Irma Fuller, Ed’s health aide, to go downstairs and tell firefighters they had an unusual situation. Abe had a cell phone – at that time, to Chavie, it was still a novelty – and he called his brother Jack to explain what was happening, to say he was all right.

Then he called Chavie, and he told her that he and Ed were together, waiting for help, and before long they’d leave the building.

Chavie heard a voice in the background. Abe told her a firefighter had arrived, that he wanted them to move to another area.

“This was destiny,” Chavie says, of that meeting. “I think they were meant to be together, at the end.”

The man who helped them was Capt. Billy Burke, of the Fire Department of New York.

Billy was 46. He had close ties to Syracuse. His older sister, Dr. Elizabeth Berry, lives here, as does a younger brother, Chris Burke. It wasn’t until a couple of months after September 11 – long after the Zelmanowitz family spent days walking the smoking perimeter of Ground Zero, handing out fliers, asking again and again if anyone had seen two friends, one in a wheelchair – that Chavie’s daughter received an email from Mike Burke, Chris’s twin: his brother Billy, Mike had learned, was there with Abe and Ed.

“Destiny,” Chavie said, of that encounter in the towers. “I get the chills. They were similar, in so many ways. They were meant to be together in this one last act of helping someone else.”

Abe Zelmanowitz, Chavie said, was a devoted son who never married after his parents died, a man who always felt a deep allegiance to his family. Just a few days ago, Chavie said, a neighbor in Brooklyn told her a story she’d never heard, how the neighbor was outside one day putting up a shed, and Abe happened to be working in his garage.

Abe was good with tools. He saw the neighbor trying to handle the shed, alone. Abe volunteered to help. Side by side, they put it up.

Abe Zelmanowitz, at home: His family says he was “handy,” good with tools – and willing to help those who weren’t. Chavie Zelmanowitz Submitted image

“That’s who Abe was,” Chavie said. Abe was a favorite uncle to his nieces and nephews, the man they wanted to see at family parties, a storyteller who’d make up tales, off the top of his head, about a character he nicknamed “Skinny.”

There’s another tale Chavie particularly loves: Abe was on the bus one day when a stranger, a young man with emotional problems, went into a rage. Other passengers, alarmed at the outburst, seemed to freeze. No one knew what to do, what to say, except for Abe: He sat down with the man. Abe spoke to him in a quiet voice. The guy calmed down. At the next stop, they left the bus, together.

“Those times in life when something happens and you think: Should I do something?” Chavie said. “He always did.”

The description is extraordinarily similar to the way Billy Burke’s siblings recall their brother. He was also a bachelor, a striking man who’d dated many women and somehow managed, miraculously, to remain their friend, a beloved uncle whose nieces and nephews always wanted to visit him in New York, a writer and photographer who dreamed of someday teaching literature, at a college.

He was a guy who’d show up to visit friends – even casual friends – when they were sick, and those who knew him best agree on one thing: When things went wrong, Billy was the kind of person who seemed to do what the rest of us can only hope that we would do.

On the 27th floor, as Billy helped evacuate a burning tower, he came upon Ed and Abe. No one can say in certainty how Billy planned to get them out, but other firefighters – including the men under Billy’s command – say he ordered them to go down, that he promised he would be right behind them. What they couldn’t know, within the cocoon of that building, is what Billy had witnessed through a window: The south tower was already gone, falling with such catastrophic force it shook the ground. The north tower, at any moment, could be next.

Abe Zelmanowitz would not leave his friend Ed on the 27th floor, and Billy Burke – once he found them – made the same choice. Chavie believes Abe, Billy and Ed saw their lives in the same way, as a sequence of challenges you face and overcome. She has no doubt, absolutely none, that all three men believed they’d find a way out.

At 10:28 a.m., the north tower collapsed.

As of Friday, it’s been 14 years. Jack and Chavie have a wall covered with honors that came to Abe after his death, honors that would have astounded this simple, decent man. When Chavie looks at the wall, she thinks of how the same guy who laughed at himself in his dripping shirt and pants could elevate the safety of a friend above all else …. And how he met a fire captain, at the end, who joined him in that choice.

“A story for the ages,” Chavie said.

Jack Zelmanowitz, now 82, has been ill. Over the years, he and his wife often attended September 11 remembrance services in Manhattan. Today, Chavie said, it would have simply been too much. She’ll do her best to follow the events on television, and she’ll think of a story Jack told her about that morning, about the last time he and his brother saw each other.

They’d gone to the synagogue, early, for prayers – a prelude to the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah. Abe, straight from there, left for work. For a reason Jack’s never quite understood, his younger brother stepped toward him and hugged him hard. Often, as they parted, they would shake each other’s hand, but an embrace? Jack was moved. This was not typical of Abe.

To Chavie, in 2015: Of course. It makes sense.

As always, when it mattered, Abe knew what to do.