Sean Kirst Syracuse.com

Gregg Hansson and Billy Burke met only once. That was 10 years ago this morning — September 11, 2001 — near an elevator on the 27th floor of the north tower of the World Trade Center. Hansson was a lieutenant in the Fire Department of New York. He was looking for one of his firefighters, ordered by Hansson to watch over two stranded office workers from Empire Blue Cross and Blue Shield.

Hansson did not expect to find Burke, a captain and a superior officer, with this little group of men. They spoke for a matter of seconds. A decision was made, as much by a nod and body language as by words themselves. Burke assumed command of the civilians, while Hansson and his men resumed their harrowing journey down a stairwell. Hansson is now a captain.

What he didn’t realize then is always with him now: Billy Burke, he said, sacrificed his own life to save theirs.

“I have moments in the past 10 years when I tend to reflect, and I think the biggest and toughest one is me and my guys being alive, and Billy’s not,” Hansson said.

The north tower was burning. At 8:46 a.m., hijackers had steered American Airlines Flight 11 into the building, touching off a fire hot enough to make steel run like butter. Sixteen minutes later, a second plane hit the building’s twin. Most workers, at least those fortunate enough to have jobs beneath the flames, were on their way down or were already out. Refusing to leave the north tower was Abe Zelmanowitz, an employee of Blue Cross. Zelmanowitz made his own heroic decision: He would not go down without his colleague, Ed Beyea, a paraplegic whose wheelchair left him without any obvious way to escape.

The two civilians were discovered by Hansson and his men as they made their way upstairs, checking every floor. Even for veteran firefighters, Beyea presented a logistical problem: He was a big man. An elevator could become a death trap. And it would be a long and difficult walk to the bottom of the tower. Hansson, not yet worried about the building coming down, thought he had time to figure it out. He assigned a firefighter named Rich Billy to stay with the civilians on the 27th floor, and Hansson and his men kept going up.

Everything changed when they reached the floors in the upper 30s. They endured a moment of sickening terror: The building — one of the tallest in the world — shook and swayed like a flimsy wooden bridge in a big wind. Abruptly, the structure seemed to steady itself.

A voice on a firefighter’s radio cried “Mayday!” To Hansson, that meant one thing: Get out.

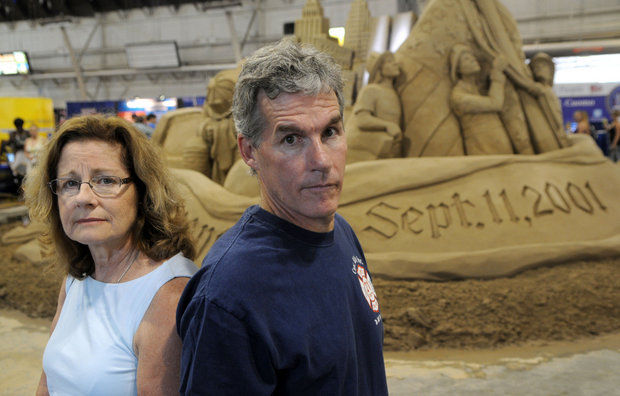

Dr. Elizabeth Berry of Syracuse (left) and Chris Burke of Onondaga (right) at the sand sculpture during the New York State Fair. The sculpture honored the firefighters, police officers and other emergency workers who responded – often at the cost of their own lives – to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Burke and Berry are siblings of Capt. Billy Burke Jr. photo Dennis Nett

Among the firefighters scattered on those floors, only a few knew what had caused the building to shake — and why they needed to evacuate, and fast.

Billy Burke, at 46, fully understood. Minutes before encountering Hansson at the elevator, Burke and another fire captain, Jay Jonas, had been searching other sections of the 27th floor when the building shook. Once it stopped, the two captains ran to windows at opposite ends of the floor, then sprinted back to meet in the middle.

“Is that what I thought it was?” Jonas asked.

“The south tower just collapsed,” Burke replied.

As it fell, that 110-floor building sent a shock wave through its twin. Jonas called out to his men and hurried toward a stairwell. He thought Burke, an old friend, was just behind him. Roughly 28 minutes later, Jonas and the others would survive the collapse of the north tower. They were in a stairwell that formed a protective bubble against the overwhelming torrent of debris.

Stunned, covered in dust and rubble, Jonas looked for Billy Burke among the survivors.

He wasn’t there. Eventually, Jonas would learn that Burke — moved by some rescuer’s intuition — never left the 27th floor. A captain with Engine 21, Burke had already ordered his own men to go downstairs to safety. Months later, firefighter Michael Byrne — one of Burke’s men — would offer testimony to the World Trade Center Task Force. Byrne would recall how Burke brought the company upstairs, a few men at a time, on one of the few working elevators. They reached the 24th floor, then climbed to the 27th.

When the building shook, Burke commanded his men to get out. The order almost certainly saved their lives. They would survive, while Byrne recalled how his captain kept promising by radio he’d “meet (them) at the rig.”

It was Hansson, back on the 27th floor, who had one final conversation with Burke.

They met at the elevator, where Burke — in his search — had already come upon the two civilians. They spoke briefly about whether it might be safe to try the elevator. Burke, who knew the south tower was already gone, had made his way upstairs on an elevator — and undoubtedly understood they lacked the time to carry Beyea, in his wheelchair, down the stairs. Hansson, who’d seen what fireballs did to elevators on the lower floors, said using one wasn’t worth the chance.

In that instant, Burke took charge of the two civilians — freeing Hansson to gather his own men and descend.

“There was an urgency in our footsteps,” Hansson recalls. Sometimes he wonders if he should have argued with Burke and tried to stay. But they had a long way to go, with no guarantee they would survive, and Burke — despite the desperate situation — never told them he had already sent his own company downstairs.

A friend to many

While Billy Burke loved his home in Manhattan, he was a regular visitor to Central New York. His older sister, Dr. Elizabeth Berry, is on the staff at Crouse Hospital. A younger brother, Chris, is a lawyer with Syracuse University. Of the many qualities Burke’s siblings admired in their brother, nothing astounded them quite as much as his gift for remaining close to his many old girlfriends without threatening the new men in their lives.

“He was very outgoing, very warm, very irresistible, with a big smile and blue eyes that were hard to resist,” said Jean Traina, an art director who for two decades designed book covers in New York City, where she often shifted between romance and a profound friendship with Burke.

“We never stopped loving each other,” she said, and September 11 offered deep proof of that bond.

As Burke and his company responded to the fire, it was Traina whom Burke chose to call four times. He warned her repeatedly to stay in her home. He asked her to tell his family he was all right. On the last call, when she screamed at him to stay away from the trade center, he simply lied to her — saying he was outside when he must have been in the north tower. She vividly recalls his last words on the phone: “This is what I do.”

From Burke’s perspective, he was born into the job. The second child in a family of six, he was the son of a deputy chief in New York. His father did not want his children in the same profession — he’d retired at 64, Berry said, worn down “by stress and smoke” — but Burke dreamed since childhood of fighting fires. Berry said her brother never forgot the lessons their dad offered about what to do inside a burning building: Get the civilians out, and then take care of your men.

Burke saw that as a family code, even as two of the world’s tallest buildings melted down.

It would be easy, then, to portray Burke as a one-dimensional lady’s man, a kind of Hollywood version of a firefighting hero, except for how profoundly that would misrepresent his essence. Women were drawn to him, yes, but Berry said her brother’s looks were only part of the attraction. He was “multifaceted,” Berry said, “literally one of the smartest people I’ve ever met in my life.”

Burke was a tremendous reader and a skilled photographer. He had written short stories, and he dreamed out loud about teaching literature at a small college. He was also an expert on the Civil War. Berry said he had enough passion and knowledge to lead informal tours of the battlefield at Gettysburg.

He gathered a vast circle of friends through loyalty and an endless willingness to share his time. During his undergraduate days at SUNY Potsdam, he worked up the nerve to ask out Gwen Webber-McLeod, now a businesswoman in Auburn. “I had an amazing relationship with Capt. William F. Burke,” she said last week. Webber-McLeod, who is African-American, describes the Irish-Catholic Burke as her “first love.” Interracial dating was hardly the norm in the early 1970s, but they stayed close even after they let go of their romance.

In 1995 — when Webber-McLeod and her husband, Tracy McLeod, learned their daughter Ashley had leukemia — Burke again became a presence. He made monthly calls to check on Ashley as the girl went through treatment and beat the disease, calls that would continue for as long as Burke lived.

That behavior was typical, said Traina, Burke’s longtime companion in New York: After Traina discovered she had breast cancer, Burke was at her side during her chemotherapy. Traina and Berry also recall a little tavern in Manhattan where Burke loved to have a beer, a place owned by an old woman named Elsie.

Burke revered her. One night, he stopped in and was told she’d grown too ill to tend bar. Burke, upset, made a few calls. He learned Elsie had been sent to a nursing home. Until she died, Burke was a regular visitor.

“He was our oldest brother,” said Chris Burke, the Syracuse lawyer, “and in life he always fulfilled that role.” Chris has a twin, Michael, who lives in New York. They were 18 months younger than Billy. The boys had plenty of brawls when they were young, but when it counted, Chris said, their brother always showed up.

Chris recalled how Billy was a center of attention in high school, a star swimmer with head-turning good looks. He was the guy every cheerleader wanted to date, the guy every other boy wanted to be. Yet he made a point of befriending smart and quirky outcasts who otherwise would have been targets of ridicule, Chris said.

“I remember he had this one friend, this little guy who didn’t fit in, and the important thing was the way Billy never made him feel that way,” Chris said. “The friendship was real. There was no contempt. He was just a guy who was always taking care of someone else.”

Sometimes, before Chris falls asleep at night, he thinks back to an autumn morning when he and Michael were seventh-graders, part of the youngest class at their new middle school. In the auditorium, an older kid pulled a pen from Michael’s pocket and threw it into a crowd of ninth-graders. The pen struck an older, much larger boy. Michael went to get it, and the kid gave him a hard shove. For a moment, the situation did not look good for Michael.

“The next thing, all you see is Billy coming through,” Chris said. “He gives the kid a right across the jaw, and the kid goes down like a ton of bricks.”

Chris choked up. He could not finish the tale. This was a big brother he describes as “bigger than life,” a big brother who — in difficult moments — always did what the rest of us hope that we would do.

‘He saved all of us’

On the 27th floor of the north tower, Hansson and Burke parted ways. Burke had taken over with the civilians, leaving Hansson and his company to descend in a stairwell, still wearing the heavy gear they’d brought into the tower.

Hansson, with four of his men, began taking the stairs two at a time, checking at every door for civilian stragglers. On the fifth floor, they came upon an office worker too tired to go on under his own power. “He was a large guy,” Hansson said, “and we were literally exhausted.” The little company refused to leave the civilian behind. They used a belt to strap the man into an office chair, and they did their best to carry him downstairs.

It didn’t work. “The chair collapsed from his weight,” Hansson said. The firefighters, sensing in some primal way that their time was almost gone, grabbed the man and began pulling him down the stairs. “I’ll be honest,” Hansson said. “We gave him a rough ride.” They finally emerged at a mezzanine, where Hansson said several police officers had managed to force open a locked door.

Without that exit, the little group would have needed to find another way out. Without that exit, Hansson is sure they would be dead. He can still describe what happened, as if he sees it playing out in front of him, once they began a desperate sprint across an outdoor plaza, toward the overhang of the nearby Custom House:

“They led us out that door, on the north side of the building, and we’ve still got this guy by the legs, and we look around and I think: ‘This is hell, what we’re in right now.’ There’s debris all over the place, and I hadn’t known people were jumping (from the upper floors) and we’re dodging them, and I threw down my mask and we’re just running. Then all of a sudden we hear this sound, this roar, and we feel like a plane is coming down on top of us …. I thought it was an explosion ….. and we go from whiteout to blackout just like that, in a second.

“The building was coming down. It was deafening and you thought it was a shock wave and obviously it was the building forcing all the air into the hole, and I said a prayer and asked God to take me quick, and I got into a fetal position. All these rocks were hitting me — I felt like it was a machine gun of rocks — and in 10 seconds or so it was over. I opened my eyes and there were pockets of fire in the courtyard and holes all over the place and I had no mask and I was choking with all the smoke and dust. I had no idea what happened, and I just thought I’ve got to get over to my guys …”

They had survived, as did the big man they rescued. The building, with catastrophic force, had disappeared only seconds after they ran out the door. Life or death, Hansson said, came down to one decision by a captain on the 27th floor: “Bill Burke’s presence — and his actions — saved all of us.”

As for Burke, he and the two civilians almost certainly died together. No one can be sure what was in his mind. Maybe he intended to gamble on the elevators, and he saw no reason for other firefighters to share in that risk. Maybe he understood a harsher truth: There would be no time to get a big man in a wheelchair downstairs, and Billy Burke wanted to save as many firefighters as he could — while refusing to allow Beyea and Zelmanowitz to die alone.

What is certain is that by ordering his own men to leave the building — and by taking charge of the civilians, which set Hansson free to go — Burke saved his own company, and Hansson’s men, and the office worker they rescued on the fifth floor.

Burke’s family and closest friends knew none of that in the hours after the towers fell. Burke had told Jean Traina he was safely outside the building, leaving her to nurture the hope he had survived. “This was Billy,” said Chris Burke. “You figured he’d get out, because he always did. You figured he’d rise from the void on the third day, walk out of there and ask you to buy him a beer, then ask the prettiest girl in the room for her number.”

Instead, silence became finality. Traina, in a city where the dust of what was lost came down like snow, secluded herself in her apartment. It was only in the following weeks — as disconnected accounts were drawn together as one story — that she and so many others who loved Burke began to comprehend the full measure of his choice.

Chris Burke has spent 10 years, in quiet moments, reflecting on the deaths of thousands in the attacks. While the pain does not recede, he has come to see a hard beauty in the decision by his brother on the 27th floor.

“Staying behind with civilians? Getting his men out first? You wouldn’t expect anything less,” Chris said. “That comes straight from our father, from our parents. He knew what was happening. He knew that thing had minutes left before it would collapse. He chose to stay. I think about it, and in my own life — with my wife and kids — you hope to carry on that sense of honor and devotion.”

Gregg Hansson, too, cannot forget. For him, at all times, the great tower falls behind him, offering a roar that chokes off air and shakes the earth. He is haunted by the idea that he should have argued about who was in charge of those civilians — even though Hansson was outranked, even though he knows what his fate would have been if he had stayed.

Not long ago, he dropped off his stepson for his freshman year of college. It was the kind of day that is emotional for any family, a powerful yet typical rite of passage, but for Hansson nothing again can ever be typical. He gave the boy a fierce hug and said goodbye, and in that simple act of love he offered thanks to Billy Burke.