Richard Fenton-Smith BBC News Magazine

After the US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, Osama bin Laden was forced to flee the city of Kandahar, where he had been based since 1997. Several compounds were hastily vacated, including one, opposite the Taliban foreign ministry, where al-Qaeda bigwigs met. Inside it, 1,500 cassettes were waiting to be discovered.

Picking through the ransacked property, an Afghan family found this haul of audio tapes, which they swiftly removed and took to a local cassette shop – with the Taliban now gone, there was money to be made producing previously banned pop music, and these were ripe for wiping and filling with the hit songs of the day.

But a cameraman working for CNN heard about the haul, and convinced the shop owner to hand the tapes back, saying what they contained could be important. He was right. This was, after all, al-Qaeda’s own audio library.

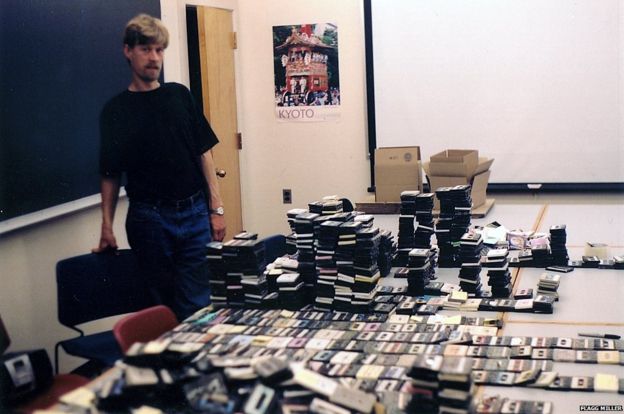

The tapes eventually made their way to the Afghan Media Project at Williams College in Massachusetts, who asked Flagg Miller – an expert in Arabic literature and culture from the University of California, Davis – to immerse himself in this hotchpotch of sermons, songs and recordings of intimate conversations. He is still the only person to have heard the collection in full.

“It was totally overwhelming,” says Miller, recalling the day he received two dusty boxes of tapes back in 2003.

“I didn’t sleep for three days just thinking about what would be required [to] make sense of it.”

More than a decade on, Miller has written a book about his findings, titled The Audacious Ascetic, which explores this unique collection. The tapes date back to the late 1960s through to 2001 and feature more than 200 different speakers – Osama bin Laden among them.

He is first heard in a tape from 1987 – a recording of a battle between Afghan-Arab mujahideen and Soviet Spetsnaz commandos. Bin Laden had left his home in Saudi Arabia, where he had been brought up in luxury, to make a name for himself fighting Afghanistan’s infidel invaders.

“Bin Laden wanted to create an image of an effective militant – no easy job, because he was known as a bit of a dandy, who wore designer desert boots,” says Miller.

“But he was very sophisticated at self-marketing, and the audio tapes in this collection are very much part of that story – the myth-making.”

The collection also features speeches given by bin Laden in the late 1980s and early 1990s to audiences in Saudi Arabia and Yemen.

“What’s fascinating is how bin Laden is speaking about the ways in which the Arabian Peninsula is threatened – but who is the enemy? It’s not the United States, as we often think, or the West. It’s other Muslims,” says Miller.

While the US would eventually become bin Laden’s prime target, there is almost no reference to “the far enemy” in these early speeches. For several years he was much more concerned with what he called “disbelief” among Muslims who did not adhere to his strict, literalist interpretation of Islam.

“They are Shia first and foremost. They are Iraqi Baathists. They are Communists and Egyptian Nasserists,” explains Miller.

“Bin Laden wanted to bring jihad to the question of who is a true Muslim.”

Audio cassettes were the perfect tool for proselytising and propaganda – it’s no wonder Bin Laden was a fan. They could be shared easily – dubbed, or passed from hand to hand – and censors paid little or no attention to them. They were also hugely popular in the Middle East and Arab world, where people would often listen to them, together with friends, formulating revolutionary ideas.

While sermons and speeches dominate this collection, there are curiosities, too. Among them is a conversation with a genie – or Jinni, in Arabic – who has taken over the body of a man. Speaking through him, he claims to have knowledge of political plots, although bin Laden is said to have had no time for such superstition.

There’s also a recording of Afghan-Arab fighters – Arabs fighting in Afghanistan against the Soviet invasion force – having breakfast at a training camp in late 1980s. This candid conversation reveals the humdrum nature of life on the front line. The conversation is dominated by the yearning for a good meal and the culinary delights of “Mr Hellfire” – a famous chef in Mecca, known for his delicious desserts.

There are also hours of Islamic anthems – songs featuring dramatised battles, and musical messages for aspiring Mujahideen. A key recruitment tool.

“For many, this is the way into jihad – through the heart,” says Miller.

“These songs have an emotional draw, bringing home the sound of combat many would read about and see on TV – there’s something intimate about hearing them in your headphones because they really play on your imagination.”

What about Phil Collins? Any Fleetwood Mac or the Rolling Stones? Unfortunately not – but Western pop music does make an appearance in the form of Gaston Ghrenassia, who usually performed as Enrico Macias, an Algerian Jew who first found fame in France, before achieving worldwide success in the 1960s and 70s.Bin Laden a fan of French pop music?

“I think this collection of French songs reveal the extent to which Afghan-Arabs in Kandahar spoke many languages, and had many world experiences. Many had lived in the West for long periods and it can’t be said enough that they had led multiple lives,” says Miller.

“These songs suggest that that someone, at some point in their life, was enjoying the songs of this Algerian Jew – and may have continued to enjoy them despite other struggles that clearly would have suggested doing so was heresy.”

Another unexpected name to make an appearance in the tapes is Mahatma Gandhi, who is cited as an inspiration by Osama bin Laden in a speech made in September 1993.

This is also the first speech in the collection in which bin Laden calls on supporters to take action against the US… by boycotting its goods.

“Consider the case of Great Britain, an empire so vast that some say the sun never set on it,” says bin Laden.

“Britain was forced to withdraw from one of its largest colonies when Gandhi the Hindu declared a boycott against their goods. We must do the same thing today with America.”

Bin Laden also encourages his audience to write letters to US embassies, to raise concern about America’s role in the Middle East conflict. Still no mention of violence against America. Foundation

“That changes in 1996, days after he is exiled from Sudan,” says Miller.

“Under US pressure he is stripped of his Saudi citizenship in 1994 and he has also lost all of his money and so he’s at his wits end. And so bin Laden has to come up with something desperate to galvanise his extremist supporters, and that’s done in his 1996 speech from Tora Bora.”

Holed up in the Hindu Kush, this speech is often called bin Laden’s declaration of war – but having gone through a complete recording of the speech found in the collection, Miller says this is not entirely accurate.

“The last third of this speech is 15 poems, and many times when this speech is translated, the poetry gets dropped out. Because of this, we don’t appreciate the extent to which this speech wasn’t a declaration of war, as it was framed by the media at the time.

“It’s about the urgency of taking on the United States, but in light of a far greater struggle – the struggle against Saudi corruption.”

It’s only in one of the final recordings found in the collection that there is any allusion to 9/11, in a recording of the wedding of Osama bin Laden’s bodyguard, Umar, which was taped a few months before the attacks on New York City and Washington DC.

“There’s a lot of mirth on the tape and then bin Laden comes up, and it’s no longer mirth. He talks about how celebration is important, but it mustn’t overshadow more austere issues.”

Bin Laden then makes an ominous reference.

“He talks explicitly about ‘a plan’ – he doesn’t reveal details – and how we are ‘about to hear news’ and he asks God to ‘grant our brothers success’,” says Miller.

“I understand that to signify the 9/11 attacks [because] he is talking specifically about the United States at that juncture.”

It’s curious that across more than a decade of recordings which feature Osama bin Laden, the thing he is most commonly associated with – terrorist violence against the West – gets such little mention.

“Al-Qaeda’s primary enemy on most of these tapes, most of the time, is Muslim leaders,” says Miller.

“Al-Qaeda’s continued presence in Yemen, its effects in Iraq, and its ongoing devastation of Muslim lives in the Muslim world only confirms the fact that this organisation, this idea, claims many bloody paths.

“There is nothing inevitable about 9/11 on these tapes. It was hard working on these tapes to remind myself of that.”

You can hear the documentary The Bin Laden Tapes on BBC Radio 4 on Monday, 17 August at 20:00 BST and on the BBC World Service from Tuesday, 18 August. Or catch up afterwards on iPlayer.