By Jonathan O’Connell Washington Post

When the people of this city set out to rebuild the World Trade Center after September 11, they planned to erect a lasting memorial, remake the skyline and restore Lower Manhattan as a financial center.

But when the 104-story One World Trade Center officially opens for business Monday – the tallest and most expensive building in the Western Hemisphere – it will have ushered in a rebirth of lower Manhattan as a vibrant, urban neighborhood where people live, shop and eat, rather than just hustle home from white collar jobs.

While officials and developers battled over final details of the reconstruction in recent years, the neighborhoods around Ground Zero blossomed. Though finance and accounting firms including Deloitte & Touche and Fidelity Investments have not returned in any significant way, hordes of condo buyers arrived, attracted by walkable neighborhoods, chic bars and chef-driven restaurants.

The political battles, lawsuits and disagreements behind the reconstruction of One World Trade Center have been well chronicled over the past decade.

But the way in which the violent attack on New York City 13 years ago ultimately spawned an urban revival is much less appreciated.

The population in the neighborhood tripled. Celebrity chef Tom Colicchio, Keith McNally and Joël Robuchon announced plans to open nearby. And on Monday, one of the standard bearers for posh Manhattan – Condé Nast, purveyor of the New Yorker and Vanity Fair – will move into the tower, occupying 1.2 million of its 3 million square feet.

“The old Lower Manhattan and the old World Trade Center was a typical nine-to-five neighborhood. It was our parents’ or grandparents’ Lower Manhattan,” said Scott H. Rechler, a real estate developer who is vice chairman of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which developed the building. “This is a 24-hour, seven-day-a-week, vibrant business district with a diverse group of tenants and a lot of creative, Millenial-type workers.”

Last week, as workers took down some of the final construction fences from around One World Trade Center and five trucks full of office furniture arrived, the question wasn’t so much how the $3.2 billion project could save downtown New York but whether it could bring it up another level.

The summer before the attacks, Port Authority officials thought they had largely extracted themselves from the real estate businesses when they agreed to lease the two towers of the previous World Trade Center to private developers for 99 years.

Six weeks later the towers were smoldering rubble, and Lower Manhattan looked like a war zone. The port authority [sic – Port Authority], which lost 84 members of its staff in the attacks, still owned the 16 acres of land on the site.

“It really was this period of breaking it into phases,” Rechler said. “A period of mourning and patriotism and cleaning it up. And then a period of what are we going to do with it. And then, how are we going to do it.”

A year later the developer that had bought the lease, Silverstein Properties, began plotting some 10 million square feet of new offices to replace the twin towers.

Silverstein’s architects, from Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, remained in place to design One World Trade Center even though another architect, Daniel Libeskind, had been named master architect of the entire complex.

But the idea that commercial office space should be rebuilt at Ground Zero at all bred early distrust for public officials, said Lee Ielpi, who lost his son, a firefighter, in the attacks and is now board president of an association of victims’ families.

The memories of what happened that day were still so raw. For years, rescue and construction workers continued to find body parts there, each a reminder that the 16-acre site still held the remains of many of the nearly 2,800 [2,749] people that died there, hundreds of whom were never found.

How could anyone think about building a project there to make money?

Ultimately, Ielpi said the port authority [sic – Port Authority] and the city provided enough space and money for the 9/11 memorial and museum that most families felt at peace with the glass-skinned office building coming out of the ground next door.

“I always felt that we do need to rebuild,” he said. “We do need to have a large memorial but in my eyes not rebuilding something big would in some way show these terrorists that they had succeeded in some way.”

Still, no one would have moved into the building had they feared the new tower wouldn’t be safer than the old ones.

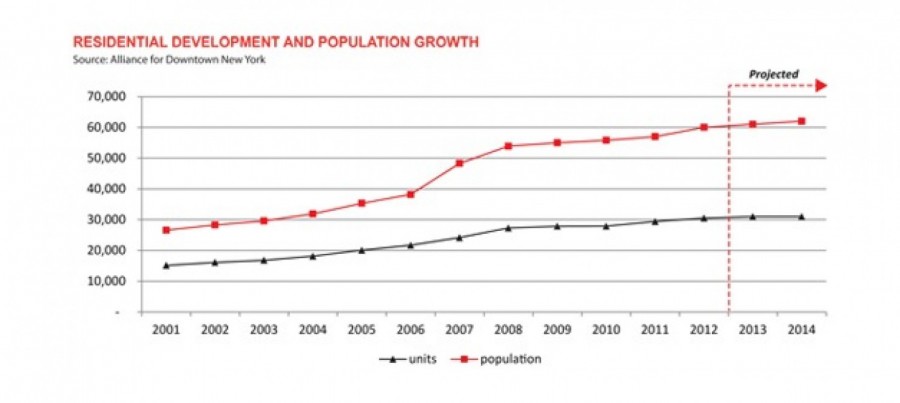

The number of people living in Lower Manhattan has tripled. (Alliance for Downtown New York)

After consulting with the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security and local police forces, architects added a 20-story fortress-like base of concrete and steel that contains mostly building systems and few offices.

The perimeter of the building is comprised of 24 steel columns, each 60 feet long and weighing 70 tons. A concrete core more than a meter thick encases its elevators and stairwells. In all, the building includes 45,000 tons of structural steel and 208,000 cubic yards of concrete, much of it four times stronger than what is typically used in sidewalks.

“One of the things that was most salient was that it was built at a time when we had to move past the current building codes,” said T.J. Gottesdiener, managing partner of SOM’s New York office. “In this era of safety, fighting fires and evacuating occupants had a different meaning to it.”

Patrick J. Foye, executive director of the port authority [sic – Port Authority], called the building “the most secure office building in America.” The final price tag for redevelopment of Ground Zero, including a transportation center scheduled to open next spring, could reach $20 billion.

Not all the financial firms are gone but Fidelity and Deloitte weren’t alone in moving hundreds or thousands of employees out of downtown after the attacks. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and Japanese banking giant Nomura inked moved to Midtown, while the Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation and others moved the majority of their employees to Jersey City.

Landlords in the neighborhoods around Ground Zero were largely left to either drop the rents or empty their buildings and convert them to apartment buildings.

Both strategies introduced new energy. The population of Lower Manhattan has tripled, from 20,000 to 60,000, with thousands of residents living in newly built or renovated condominium towers. Another 2,200 units in 10 buildings are under construction, according to the Alliance for Downtown New York, an association of building owners. Media, advertising and technology companies began snapping up the discounted office space, bringing a more creative workforce downtown.

Chuck Townsend, chief executive of Condé Nast, said “there is a great deal of pride” in being the largest renter at One World Trade. He likened the company’s move to its relocation 15 years ago into Times Square, known at the time more for pawn shops than high-end offices.

About 3,000 employees will work in One World Trade Center, on floors 20 through 44, with the move-in complete by early 2015.

“We pioneered Times Square and I’m telling you it was no jewel at that time,” he said. “In a way it was a much more challenging move than moving into this well-developed, well-cultivated neighborhood where there are beautiful offices and residential buildings and a gorgeous park and a wonderful memorial.”

Even with Condé Nast, One World Trade Center is only about 60 percent leased – a potential cause for concern – but Time Inc., book publisher HarperCollins and Macmillan Science and Education, publisher of Nature and Scientific American, have all made or announced moves downtown recently. Office leasing activity for the first half of the year was 43 percent higher than last year.

“This was an area that was quiet, where people had gone home after around six o’clock. Now this is probably one of the most attractive parts of Manhattan for people to be, and I think companies are recognizing that,” said Foye.

Salons, gyms and restaurants are following suit. Eataly, the Italian food marketplace, plans to open in 4 World Trade Center. “Restaurateurs think, ‘We want to be the lunch room for Condé Nast, so if we don’t have a downtown location we should open one,’” said Jessica Lappin, president of the downtown alliance [sic – Downtown Alliance].

It may take longer for New Yorkers to get used to the change to their skyline than it did for them to adapt to the changing vibe downtown. Blair Kamin, architectural critic for the Chicago Tribune, recently called the building a “bold but flawed giant.”

Ielpi, father of the firefighter who died in the attacks, said he considered the building a “beautiful piece showing our country’s resolve.”

“We had to bring commerce back to the city. We had to show our strength. This is the center of the universe. So I’m very proud of One World Trade Center, but as soon as we forget why we had to rebuild it we have failed.”