Joe Neumaier New York Daily News

To see a trailer for the movie, please click here.

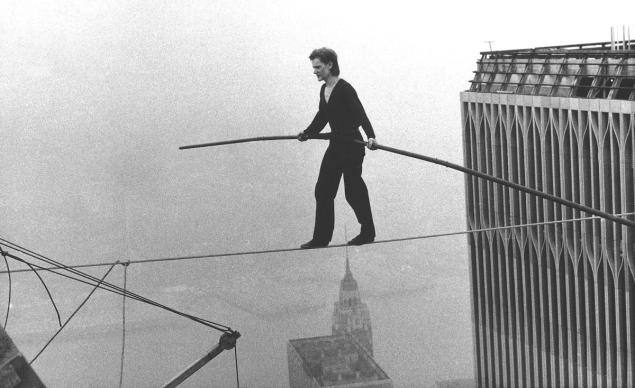

It took high-wire walker Philippe Petit several years and a band of cohorts to plan and pull off his death-defying, 45-minute tightrope walk between the nearly completed World Trade Center towers on August 7, 1974.

Philippe Petit attends the New York Film Festival opening night gala premiere for “The Walk” at Alice Tully Hall on Saturday, September 26, 2015, in New York. Charles Sykes/Charles Sykes/Invision/AP

But it took director Robert Zemeckis almost nine years, and dozens of movie magicians, to recreate Petit’s sky stroll for the new film The Walk, opening Wednesday.

This time, we all come along for the trip.

“The camera here is sort of a dance partner with Philippe,” says Zemeckis. “Out on the wire, the movie becomes like a dance.”

Says Petit, “It’s a special work because of the way the camera invites you to walk by my side. It brings the viewer on the wire with me.”

Despite the infamy of Petit’s extraordinary, and illegal, adventure — the years of planning, the sneaking up to the towers to scope them out, the turns of luck that went in his favor as he set off from the south tower on that overcast August morning — The Walk, in fact, breaks new ground in an unexpected way.

“In 1974 Manhattan, in the 45 minutes Philippe was on the wire 100 stories up, no one could scramble to get a movie camera,” says Zemeckis. “It was a big deal in those days to get a film camera at the last minute, so there’s not a single moving image of him up there!”

Petit acknowledges the historical quirk. There are photos from his accomplices and from bystanders below — as seen in the 2008 documentary, Man on Wire —- but no filmed document.

Philippe Petit, a French high wire artist, walks across a tightrope suspended between the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers. New York, Aug. 7, 1974. Alan Welner/AP

“My friends had a 16mm movie camera ready and loaded on the north tower, but the police came,” says Petit. His sentence, after being booked: Perform a free wire-walk in Central Park — during which he nearly fell.

For The Walk, Zemeckis more than makes up for that day’s lack of footage. The filmmaker, whose technical innovations include the Back to the Future trilogy (1985-’90), Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), the Oscar-winning Forrest Gump (1994) and The Polar Express (2004), knew the best way to turn Petit’s iconic act into a movie was to make a cinematic leap, and to do in 3D.

When Zemeckis first spoke with Petit about making the film, adapted from the French acrobat’s 2002 memoir, To Reach the Clouds, the director was toying with filming Petit in a motion-capture outfit (and having him play every character in the film).

That version fell away, and a more straightforward approach was chosen. Zemeckis and visual effects supervisor Kevin Baillie set about animating Joseph Gordon-Levitt at tricky moments on the wire, with the actor’s face on the body of a Cirque du Soleil performer, and digitally turning the Montreal set into Paris and New York.

Then came recreating the Twin Towers, in eye-popping, photorealistic perfection.

“That was tricky because everybody has a different idea of what the towers looked like,” says Baillie. “Because they had an anodized aluminum skin, they were like chameleons. On a sunny day they looked white, on a cloudy day they looked darker.

“And because they took on the environment around them, we had to think about what would also be in the camera’s view. If Manhattan was too dark on our digital horizon, it would then make the towers look too dark. We had to think about what was ‘behind the camera,’ in a way.”

That was for the outside. They also had to look inside.

“In some of our countless reference photos, you can see desks and lamps inside office windows, so we built digital interiors for the bottom 30 floors and the top 30 floors,” says Baillie. “Especially in 3-D, you can see desks and blinds, or paint cans, as if a construction worker hadn’t gotten there yet.

“Yet the only thing real is the actual wire, Joseph Gordon-Levitt on that wire and a 60-by-40-foot section of the top of the roof.”

That sense-surround was crucial to Zemeckis.

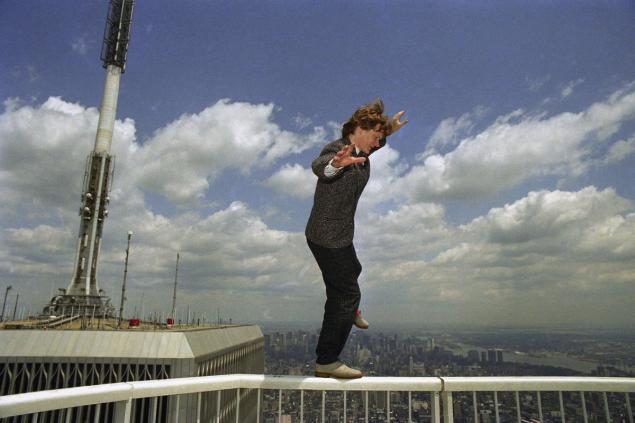

High wire artist Philippe Petit walks the railing atop New York’s World Trade Center, 1,350 feet above Manhattan’s streets on July 14, 1986, during a break in a news conference held to announce his dare-devil plans for the rest of the year. Included in Petit’s future exploits is a high wire walk over the Grand Canyon next spring. Richard Drew AP

“I wanted everything in the movie to look real, and as it looked on August 7, 1974,” Zemeckis says. “We used the most sophisticated digital technology available. The digital team talked to people intimate with the construction, and they had almost every photograph ever taken of the tower.”

“If we made the towers as perfect as blueprints, they’d look fake,” says Baillie. “The construction workers didn’t align every panel. So we made some slightly off-kilter, but not too much.”

The human element of the walk was just as critical, and for that, Gordon-Levitt trained with Petit for eight days to learn his craft.

“In those few days with me, not only did Joe learn how to walk a wire 7 feet high and 30 feet long, but he got to observe my way of being, my speech, my manners,” says Petit.

The actor says the man today is different from the one who mesmerized New York.

“Now he’s more mellow, but when Philippe was 24, there was a slightly narcissistic side to him,” says Gordon-Levitt. “When he got up on the wire, though, he was gobsmacked by the enormity of his situation, of the buildings and of New York.

“He lent the towers a charm and humanity that they didn’t have before that.”

Petit thinks The Walk puts viewers into his head as much as in his shoes.

“The genius of the movie is that it blends what’s happening in my muscles, my body and my feet, and also what was in my head,” says Petit.

“Watching the movie, I truly was on the edge of my seat. I was praying for this guy, hoping he’d make it. I forgot that, oh right, I AM the guy!”