The man who got unprecedented access to JFK’s life stored his whole archive in a safe in the twin towers. A new exhibition shows the painstakingly restored fragments that survived

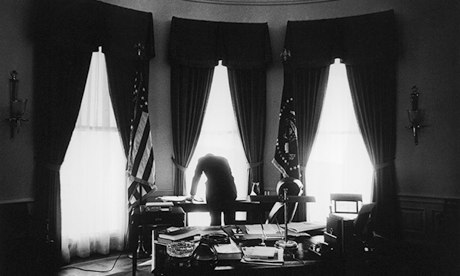

A silhouette of President John F Kennedy in the Oval Office, May 1961. © Estate of Jacques Lowe, 1961

What do you do when, as a photographer, you are told your image archive is so precious that it’s uninsurable? The answer for Jacques Lowe, whose images helped create the legend of John F Kennedy, was to store them in JP Morgan’s seemingly impregnable vault in Tower 5 of New York’s World Trade Center. But then 9/11 came, and his life’s work went with it.

After the terror attack, Jacques Lowe’s daughter, Thomasina, campaigned to try and retrieve her father’s archive from the twin tower’s rubble before they were razed. Amazingly, the safe in which they were stored was found intact, but the contents – over 40,000 negatives – were reduced to ash. All was not completely lost though, as 1,500 of Lowe’s contact sheets were located elsewhere in New York. From these, selected images were painstakingly restored for an exhibition at the Newseum in Washington DC. A collection of prints from the original negatives were also made by the photographer himself, prior to his death four months before 9/11. An exhibition at Proud Chelsea in London is now showcasing these rarities.Jacques Lowe became John F Kennedy’s presidential campaign photographer in 1960 and, after his election victory over Richard Nixon, became the first family’s personal photographer after turning down an official White House photographer role. It was a wise decision to decline the restrictive job on staff in favour of unprecedented access to the family both in and out of Washington. Kennedy’s term in office became known as one of the most captivating periods of 20th-century US history, and Lowe was on hand to document what went on behind the scenes.

Senator Lyndon B Johnson, Robert F Kennedy and John F Kennedy discuss the vice presidential nomination at the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles, July 1960. © Estate of Jacques Lowe, 1960

The images are familiar: in one, Kennedy’s brother and campaign manager, Robert, looks decidedly unimpressed by his choice of running mate, Lyndon Johnson.

It has been claimed that Johnson blackmailed Kennedy into offering him a place on the ticket after threatening him with evidence of his womanising, provided by the FBI director J Edgar Hoover.

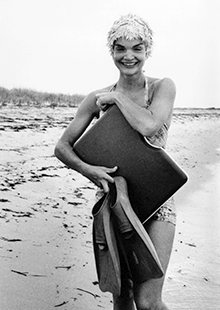

Jackie Kennedy at the seaside near their holiday home in Hyannis Port, Massachusetts, August 1960. © Estate of Jacques Lowe, 1960

In another image, Jackie Kennedy flashes Lowe a warm smile as he snaps her in swimwear on a seaside break.

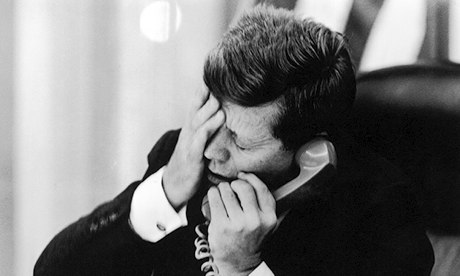

But most notable are images that show how close Lowe got to Kennedy, such as the shot that captures the moment when he heard Patrice Lumumba had died. Lowe’s 1983 book, Kennedy: A Time Remembered details that moment: “On February 13 1961, United Nations ambassador Adlai Stevenson came on the phone. I was alone with the president; his hand went to his head in utter despair, ‘Oh, no,’ I heard him groan. The ambassador was informing the president of the assassination of Patrice Lumumba of the Congo, an African leader considered a trouble-maker and a leftist by many Americans. But Kennedy’s attitude towards black Africa was that many who were considered leftists were in fact nationalists and patriots, anti-West because of years of colonialisation, and lured to the siren call of communism against their will. He felt that Africa presented an opportunity for the West, and, speaking as an American, unhindered by a colonial heritage, he had made friends in Africa and would succeed in gaining the trust of a great many African leaders. The call therefore left him heartbroken, for he knew that the murder would be a prelude to chaos …”

President Kennedy hears of the assassination of Patrice Lumumba, February 1961. © Estate of Jacques Lowe, 1961

Disillusioned after Kennedy’s 1963 assassination and the further shootings that claimed the lives of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the German-born Lowe returned to Europe in 1968. His Kennedy negatives meant so much to him that he bought an extra seat for them on the plane to France. And 33 years later, another aeroplane was to decide the fate of the images that had defined him as a photographer.

Jacques Lowe: My Kennedy Years, is at Proud Chelsea until 24 November 2013