By Arnie Weissmann Travel Weekly

Travel Weekly

More than 700 members of the travel industry — agents, tour operators, destination marketers, hoteliers, cruise line officials, car rental executives, technology providers — gathered in New York last week. The occasion was Tourism Cares’ 10th anniversary celebration, with a gala on Wednesday night and, on Friday, a hands-on restoration project to repair damage inflicted by Hurricane Sandy on Coney Island and Fort Tilden in Queens.

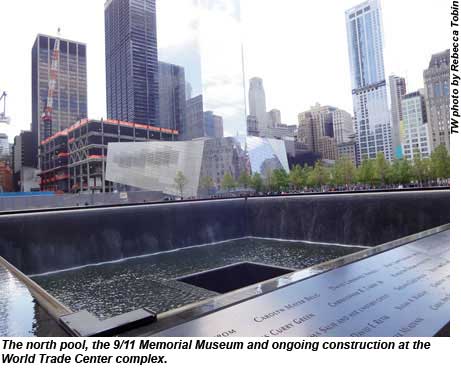

Between those two events, volunteers for the restoration effort were invited to a special ceremony on Thursday at the North Pool of the 9/11 Memorial at Ground Zero to honor victims, first responders and the families of those affected by the tragedy.

I’m on the board of Tourism Cares and participated in all the events. But I began the week in Jerusalem. Last Tuesday, I moderated a panel at the Jerusalem International Tourism Summit. It turns out there was a connection between that event and what I would be doing two days later in New York.

I had been very much looking forward to hearing the speaker who followed my panel in Jerusalem, the architect Daniel Libeskind. In the past 12 years, Libeskind has built a reputation for interpreting public spaces in striking and unusual ways, layering meaning onto form in a manner that evokes both an emotional and contemplative response. It was he who was chosen to design the master plan for Ground Zero, a plan adopted despite having generated considerable controversy.

Paradoxically, Libeskind’s very first building, the Jewish Museum in Berlin, opened on September 11, 2001. That structure characterized many of the themes that have informed his work since then, with symbolic use of light as a mirror for enlightenment and vertical space, from the subterranean to lofty heights, to convey a sense of both the depth of emotional foundation and soaring hope for an optimistic future.

I have always been struck by his designs and his attempts to relate buildings with not only their physical surroundings but with their deeper meaning, whether it is the Denver Art Museum or the high-end shopping mall that fronts Las Vegas’ City Center. I arranged to interview him following his address in Jerusalem.

His speech, “Architecture and Tourism,” was a quick review of his best-known public projects around the world, and how in some cases, they have increased tourism or revived urban areas.

In my interview with Libeskind, I focused on how he approached the 9/11 master plan. He provided me with insight not only into how he came to view the project, but into the relationship between a building and the visitors who come to see it. What follows are excerpts from our conversation:

Daniel Libeskind: I think [the 9/11 site] will be the most-used public space in America, maybe in the world. Already millions of people have come to the memorial, and it’s still a construction site. When the streets are opened, when the buildings are finished, when the museum is finished, this will be redefining New York for the 21st century. Never mind the aesthetics of individual buildings. I tried to create a community, a sense of place, a sense of symbol, a sense of belonging, a sense of social space, urban space.

Arnie Weissmann: You may approach a project like this with a very philosophic approach, projecting symbolic meaning onto physical space. But for a lot of visitors, it will be seen in more basic terms, as a tourist attraction. Does the phrase “tourist attraction” have a pejorative connotation to you?

Libeskind: Not at all. Tourists are smart. People who come to the Jewish Museum in Berlin, most of them are not Jews, but they learn something. They learn by the geometry of the building, the space, the light, they learn something that they really want to know. People are interested in profound things. And everybody, at whatever level of education, has desire to know something that is true about a place.

And so, whether it is that the Freedom Tower is 1,776 [feet tall], or the significance of the Wedge of Light [between structures], every building can communicate something profound to tourists. That’s why tourism grows [as a result of architecture].

The people who commissioned me to do the military museum in Dresden said, “You know, we have very few visitors. Nobody is interested in the military.” But they had a million visitors in the first year [after the redesign]. So people are interested if you do the right kind of thing. People are thinkers. People are creative. Tourists are not just consumers. They are people with souls, and you have to connect in a profound way.

Weissmann: Does it matter whether people have a conscious idea of what you set out to do?

Libeskind: No. It’s like listening to Bach. You might not know how complex it is, what is in the music, but you can enjoy it, and when you enjoy it, you find there is something more to the music. And they enjoy it even if it’s provocative. The provocation itself is important. You’re jolted out of your comfort zone, of your normal sense of “This is what I expect a museum to be.” Projects have to take a risk, to be bold. Rather than anesthetize people, they have to shift the perspective. And it’s possible to shift perspective, even in large urban spaces in New York, absolutely.

Weissmann: Your design was controversial in part because so much of the space is left relatively open, and parts of it are underground. Why?

Libeskind: You know, I was with the architects, the final seven left in the competition. And we were all in a meeting at the Port Authority looking down at the site, 1 Liberty Plaza, and someone offered to take us down to the site. It was a miserable, rainy November day. And everybody else said they could see it very clearly from where we were, looking straight down. But I went and walked down with [my wife] Nina, and as I walked the ramp 75 feet down, I felt like somebody who is diving to the bottom of the sea. The pressure, the notion of where you are became real.

That’s where my life changed. I suddenly realized what it means when 3,000 people die in a place. I thought this should be made visible to the public. I called from the site to my office, which was still in Berlin. I said, “Forget all the plans. Nothing should ever be built on half of the site.”

That’s eight acres. The [entire] site is 16 acres. It’s a small site, and it was hard not to build on half it and still accommodate 10 million square feet of office space. It’s hard because everybody puts buildings where there is space for them. But I decided not to do that, and I think New Yorkers were with me. Nobody had declared the site a spiritual site, but I thought we could bring people here and give them a sense of something positive, not just something negative. I left the slurry wall, the foundation, exposed because the world changed after these events, and foundations are made to be built upon. That will become the September 11 Museum.

It’s a different world [since 9/11], and you can never get that from watching TV, watching movies or reading about it. You will get it, truly, when you come down to this bedrock from which the buildings are really constructed.

If you have a memorial, people are sad, and I never wanted that. But if you see that the museum is also a foundation, you see how New York has been constructed, and that’s a reference to the past, but also moves New York forward. It’s a great, incredibly imaginative, fantastic, fun city. You can use the history as something inspiring.

Weissmann: Was it from being on the ground or from looking at plans that you saw the opportunity to face the Hudson River and incorporate the Statue of Liberty?

Libeskind: I was on the bedrock, as I saw — this is true — I saw myself and my mother and my sister coming on a ship and we came by the Statue of Liberty, and I said to myself, “That is the key.” [Editor’s Note: Libeskind immigrated to New York from Poland, by ship, in 1959.] New York is about immigrants; it’s what New York stands for. [The Statue of Liberty] is a symbol, and it’s not a hollow symbol. I use it in the buildings, as elements of the composition. Instead of having one building, I used the buildings to create the torch-like movement that rises from low to the height of 1,776 feet to create this flame of memory at the center of the site where the waterfalls are. I built this toward the Hudson River, not toward [the] Wall Street [area], where there are a lot of dark streets. I thought about the sense of community and of the beauty of New York and of the inspiration of New York and about life.

Weissmann: Were there changes to your original plan?

Libeskind: Very few. Very, very few. I made the buildings certain heights. I gave them a certain footprint so that it wouldn’t be too large, so there would be a lot of public space. I composed the buildings to create a sense of something important. So it’s very close.

Weissmann: When you first saw the actual Freedom Tower physically …

Libeskind: Ah, fantastic! It was a great moment. It’s a new skyline. The [height of the spire] will never be surpassed, even if they build a taller building in Nigeria or India. It will never be surpassed, because it’s not the height of a building that counts but the height of aspiration. What it needs.

And that’s what America is about. It’s about freedom and liberty and democracy. That’s what that site is about.