By Wayne Coffey New York Daily News

Brielle Saracini & Derek Jeter

More than just about anything in life, Brielle Saracini wanted to be at Derek Jeter Day. After all that he has done — very quietly — for her and her family over these last 13 years, how could she miss his day?

As soon as the date was confirmed, Saracini went on line and bought two tickets. She was going to go with her close friend, Louis Verdi, making the trip up from her home in Yardley, Pa. It was going to be one more way to thank Derek Jeter, to celebrate a goodness that Brielle Saracini can appreciate in a way that almost nobody else can.

“I’m one of the lucky few to have a special connection with him,” Saracini, 23, says. “He’s so much more than a baseball player to me. He’s a mentor. He’s someone I look up to, because of the way he treats people.” She pauses for a moment.

“He is someone who has helped me through a lot of dark times.” Says Jeter, “(Brielle) has been tested numerous times and lived through quite a bit. She’s a very strong person.”

With 21 days and 21 regular-season games remaining, the epic, 20-year career of Derek Sanderson Jeter will be celebrated at Yankee Stadium Sunday, the most famous baseball franchise of them all saluting the staggering achievements of a man who has spent half of his 40 years wearing No. 2, making it as storied as any other Yankee single-digit number.

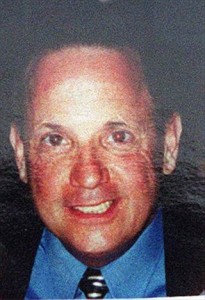

Victor J. Saracini, AP

Amid all the tributes and tears that will no doubt mark the occasion, you can be as sure as traffic jams on the Deegan that there will be a big-screen retrospective of the definitive baseball moments of Derek Jeter, culled from the 2,733 regular-season games he has played, or the 158 postseason games, across 33 series, that he has been a part of.

You will see the fabled flip play that kept the Yankees alive in Game 3 of the 2001 ALDS against the Oakland A’s, Jeremy (Don’t Slide) Giambi lumbering home, Jeter somehow anticipating an overthrow and retrieving the ball by the first base line before shoveling it backhand to Jorge Posada.

You will see his dive into the stands to steal an out against the A’s Terrence Long two games later at the Stadium, and an even more famous dive, basically full speed, that resulted in a battered face, a standing ovation and an out against the Red Sox on July 1, 2004.

From the early years, you will probably see 21-year-old Jeter hitting his first career home run, on Opening Day, 1996, a blast off the Indians’ Dennis Martinez, Jeter rounding the bases as if he’d done this many times before, head down, not a single check-me-out antic in sight, and you will definitely see his 237th home run, which came 15 years later, off of David Price. It also happened to be his 3,000th career hit, part of a 5-for-5 afternoon against the Tampa Bay Rays three summers ago.

And without a doubt the tribute will include the midnight home run Jeter hit in the 10th inning of Game 4 of the 2001 World Series against the Diamondbacks, the windup of a nine-pitch at bat against Byung-Hyun Kim, a trademark opposite-field shot that tied the Series at 2-2, and gave Derek Jeter a new nickname: Mr. November.

All of these highlights, and more, will likely be rolled out, and why not? They constitute the essence of the smart, clutch, selfless, team-first persona that is at the core of who Jeter the ballplayer is. And yet, if you ask Rob Gilbert, none of the clips truly speak to the reason that Jeter has become the iconic figure he has become. That reason, says Gilbert, a sports psychologist and professor at Montclair State University, is his utter, and unparalleled, consistency, on the field and off of it.

“From an overall perspective, Derek Jeter has done something no baseball player has ever done,” Gilbert says. “He might have made some errors on the field, but he has never made any errors off the field. With all the social media these days, all the paparazzi, everybody watching him, he never screwed up once. We may not see another like him.”

Gilbert likens Jeter to the “most successful franchise this country has ever known” — McDonald’s.

“I’m not talking about food value,” Gilbert says. “I’m talking about this same quality — consistency. You can go to any McDonald’s in the country and the hamburgers taste the same and the French fries taste the same. There are never any surprises. And that is how it is with Derek Jeter. Never any surprises, from the first workout in spring training to the last out of the World Series.”

To Gilbert, ours is a culture that is built on the Instagram model of celebrity, athletic wiring designed to maximize SportsCenter coverage, sizzle vastly outdistancing substance, as epitomized by the Johnny Manziels and Yasiel Puigs of the world.

Derek Jeter is your father’s superstar. He is Yogi Berra’s superstar, a man whose M.O. is understatement — a man who doesn’t want to trend.

Only win.

You think it was by chance that whenever Berra would visit the Stadium, one of his first stops would be Derek Jeter’s locker? There would be a handshake, or a hug, some good-natured banter about rings, Yogi tweaking Jeter about his 10, and five in a row. When the Yankees fell short against Arizona in Game 7 in 2001 and had their streak stopped at three, Yogi told Jeter, “You have to start over now.”

There isn’t a Yankee that the 89-year-old Yogi Berra respects more than Derek Jeter.

“He’s always been a good kid,” Berra says. “He plays the game right. He’s had a great career and he is a great Yankee.”

Brielle Saracini, who has no World Series rings, could hardly agree more. She has her own reasons for revering Derek Jeter.

They trace to September 11, 2001.

BRIELLE’S PAIN

One week into fifth grade in Quarry Hill Elementary School in Yardley, on the second Tuesday of September 2001, 10-year-old Brielle Saracini was in Ms. Tiso’s class when United Flight 175, bound from Boston to Los Angeles, took off from Logan Airport, a bit behind schedule, at 8:14 a.m.

On board were 51 passengers, nine crew members and five terrorists. Armed with knives and mace, the terrorists would storm the cockpit, stab crew members and hijack the Boeing 767, United Flight 175 terminating at 9:03 a.m., at the South Tower of the World Trade Center.

One of the first confirmed fatalities was the pilot. His name was Victor Saracini. He was Brielle Saracini’s father, and her sister Kirsten’s father, and mother Ellen Saracini’s husband.

And so began the worst time the Saracini family will ever know, a blur of pain and grief that often left them wondering if they could possibly make it through the next few seconds. Ellen Saracini tried hard to protect her daughters from any more agony than they were already going through, and one rule she was decided on was: no television. The only exception was baseball games. Brielle, especially had become a huge fan of the Yankees, and their 27-year-old shortstop. It started when Brielle read a book called “The Life You Imagine” that Jeter wrote with co-author Jack Curry, then with The New York Times, now with the YES Network. Brielle loved the respect and devotion Jeter showed towards his parents in the book, and the discipline and hard work and humility he wrote about.

“I just became enthralled with him, and I became obsessed with baseball, especially Yankee baseball,” Brielle Saracini says. When she went back to Quarry Hill for school on September 12 — it was better than sitting at home — Brielle wore her Yankee hat. School authorities decided to waive their no-hat rule for her, considering the circumstances. Brielle wore the hat everywhere.

“I felt invincible when I had it on,” Brielle Saracini says.

Not long after September 11, Brielle went up to her room one day and wrote a letter. She came down and asked her mother, “Do you know the address for Derek Jeter?”

Ellen Saracini asked her daughter why, and she said she’d written a note to him that she wanted to mail.

“I had no knowledge of her doing it. It was just something she felt very strongly about doing,” Ellen says.

Says Brielle, “It just made sense at the time. You are 10 years old, and you idolize a person. You are experiencing (an excruciating loss). I thought, ‘What’s the one thing that could make me feel better?’ ” Brielle decided that more than anything she would like to meet Derek Jeter. Not only did that make her happy to think about, it was something her father would’ve loved.

He was always talking to the girls about going after their dreams and not letting anything stop them.

The letter began:

“Dear Derek Jeter,

My name is Brielle Saracini. As you have heard, there was a horrible accident that involved the Twin Towers, there was a hijacking on a plane. Terrible people are in this world, but you and I both know that. . . That horrible hijacking happened to my father. My father was the pilot, Captain Victor J. Saracini.”

The letter made its way to a Philadelphia TV station and then to the Yankees. Jason Zillo, an assistant in the public relations department then, took it from there, discussing it with Jeter, hatching plans. Soon the phone rang in the Saracini home. Derek Jeter was on the line.

“I don’t think I could even talk,” Brielle says. When she got off she ran around the house, singing and screaming.

“I couldn’t believe what had just happened,” she says.

Jeter expressed his deep condolences and invited Ellen and her daughters to a game — September 26, against Tampa Bay. It was a Wednesday, 15 days after the terrible people had had their way. They got to the game hours early. Brielle had her Yankee hat on, of course. Zillo met them and took them right down to the field. Jeter came over and introduced himself and gave them each a hug.

“Hi Mr. Jeter,” Brielle said. Other than that she could not speak.

“Brielle, call me Derek. Mr. Jeter makes me sound like my father,” he said.

Ellen showed Jeter the scrapbook Brielle had made about him, full of photos and stories and facts about his career, and Brielle’s imitation of his signature.

“Brielle, you sign my name better than I do,” Jeter said.

Joe Torre came over, and so did Tino Martinez and Scott Brosius, and others. Everybody was so kind, the day so perfect. Later they went upstairs and Brielle got to meet Jack Curry, who would become a close family friend. The Saracinis sat right by the Yankee dugout. Jeter batted third that night for one of the few times all season. When he came to the on-deck circle to lead off the bottom of the eighth, he called the girls over to the railing. People wondered who these girls were, and why Derek Jeter was calling for them.

He handed each girl a black Rawlings Derek Jeter glove. Once more Brielle could not speak. Jeter roped a double down the left field line. Mariano Rivera came on and closed out a 3-1 Yankee victory.

“It was the first day I saw my girls happy and smiling since their Daddy died,” Ellen Saracini says.

YOUNG DEREK

Benji Gil has his own unique connection to Derek Jeter, not because of tragedy, but a shared journey. Gil, too, was a highly touted shortstop and a first-round draft choice, not out of Kalamazoo, Mich., but Chula Vista, Calif., by way of his native Mexico. Gil was taken by the Texas Rangers in 1991, a year before the Yankees selected Jeter sixth overall. He first met Jeter at second base at a single-A ballfield in North Carolina, Gil playing for Gastonia, Jeter for Greensboro in the South Atlantic League. It was late in the 1992 season, and Gil saw Jeter in a way few people ever do: in a state of discouragement that bordered on full-blown despair.

“I could see where he was kind of wanting to go home,” Gil says.

At 18 years old, as skinny as a cornstalk, Jeter had his $800,000 signing bonus, along with deep doubts about whether he’d made a mistake by signing with the Yankees out of Kalamazoo Central, instead of accepting a scholarship to play for former Tigers great Bill Freehan at the University of Michigan.

In his first doubleheader in rookie ball that year, with the Gulf Coast Yankees, Jeter went 0-for-7, struck out five times and committed an error. He felt completely overmatched, calling home every night, often in tears, telling his parents he didn’t know if he could do this. Only a surge late in the year enabled Jeter to get his average above .200 (all the way to .202). The Yankees wanted him to keep playing, so when his rookie-ball season ended they sent him to Greensboro, where he had his chance meeting with Gil, who asked him how it was going.

“Not good,” Jeter said. “I’m really struggling.”

Gil was taken aback by Jeter’s candor, and offered a tip that Gil’s older brother had taught him. Because you play every day, baseball, above all else, is a mental grind, a sport that demands that you find strength and nourishment wherever you can.

“No matter how things are going, take something positive out of the day,” Gil told him. “If you go 0-for-4 but play good defense, that’s a positive. If you run the bases well, that’s a positive. If you make a couple of errors but hit a double in the gap, that’s a positive.”

Jeter’s parents and the Yankees had been making the same point, but hearing it from his fellow shortstop and No. 1 pick somehow made it resonate more. Gil could tell how intently Jeter was listening, could tell how much he wanted to be good.

“There are certain guys, just with the way they move, the way they carry themselves, you can tell there is something there, even when they’re not doing great,” Gil said. “That’s how it was with Derek. You could see the talent was there. You knew it was going to happen.”

Jeter’s Greensboro teammate, Mariano Rivera, knew it, too. The next year in Greensboro, Jeter’s average jumped to .295, with 11 triples and 18 stolen bases, but his defensive play — he made 56 errors — was abysmal.

The Yankees player-development people in Tampa had ongoing debates about moving Jeter to center field, the way the Yankees had done with another error-prone prodigy, Mickey Mantle, 40 years earlier. Rivera could’ve told them right then: leave him alone. He will figure it out and he will be great. For 35 straight days in the offseason, Jeter went through defensive boot camp, pounded with ground balls off the bat of taskmaster/coach Brian Butterfield.

“Derek had more focus and drive than anybody. I never had a doubt (about him),” Rivera says.

TROUBLE RETURNS

Brielle Saracini grew up, had her braces done in Yankee colors and always kept her Derek Jeter glove nearby. She stayed in touch with her favorite player. When he was in Trenton (not far from the Saracini’s home) for a rehab stint, he had her on the field, greeted her with a hug and a kiss, saying, “How’s my girl, Bri?”

At first she was a little surprised that he remembered her, that with all the fans he meets and all the people clamoring for his attention, he would seek her out. It made her feel great.

“He’s such a genuine person,” she says. “You never get the feeling he’s doing it because he has to do it, or that he’s going through the motions. You get the feeling that he wants to do it.”

Brielle Saracini went off to Boston College, got her degree and landed a job, perhaps not surprisingly, at the YES Network. It was all good until the summer of 2013. Brielle Saracini went to the doctor and had some tests done. The results came back. She was diagnosed with Hodgkins’ lymphoma. The date was Aug. 5. She started with chemotherapy almost immediately. It made her sad that Derek Jeter was having his own physical problems, his season limited to 17 games as he attempted to come back from ankle surgery. She wanted so much to see him out there playing. The season wound down. On a Thursday afternoon late in the year, she was watching a Yankees home game. Her phone was in the next room. When she checked it later there was a voicemail from someone who had called during the game.

The message was from Derek Jeter.

The date was September 26, the same afternoon Jeter and Andy Pettitte went out to the mound to take the ball from Mariano Rivera to close out his career. It was also the 12-year anniversary of the day Brielle, Kirsten and Ellen Saracini had visited the Stadium after United Flight 175 was hijacked. Even the opponent — Tampa Bay — was the same.

“I just wanted to call and say, keep your head up, stay positive and everything will work out just great,” Jeter said in the message.

Jeter has had a profoundly personal experience with Hodgkins’, his sister, Sharlee, fighting her own battle with it 13 years earlier, during her senior year at Spellman College in Atlanta. Sharlee Jeter, a math major, was studying in her dorm room one night during a Yankee game, her friends teasing her that her brother was going to strike out.

Instead, he hit a home run, and when she got up to do a little good-natured gloating, she got tangled in her books and tumbled onto the floor. She thought nothing of it, until later that night when she felt a lump in her neck.

“Maybe it was from the fall,” she told herself.

The lump didn’t go away. She went to the doctor. When she found out she had to go in for a biopsy, the baseball season was over and Derek was on vacation in Puerto Rico. He came back early to go with his sister for the testing.

“He’s always been my brother first,” says Sharlee Jeter, who is the executive director of her brother’s Turn 2 Foundation, a charity he started in his rookie year to promote education and help kids make healthy decisions. “He’s a good person, and he cares about being a good person.”

Brielle Saracini went through a course of 12 chemotherapy treatments, completing them in January of this year. A scan said that she was cancer-free. A second scan was not so heartening. In May, she found out the Hodgkins’ had come back. She started another round of even more aggressive chemotherapy. It was not an easy time. On Tuesday night, July 1, she made it to Yankee Stadium. The Yankees were playing Tampa Bay, naturally. Brielle Saracini met Derek Jeter in the tunnel near the dugout before the game. He gave her the usual hug and kiss.

“Are you ready for retirement? What are you going to do?” Brielle asked him.

“Absolutely nothing,” Jeter replied, smiling, even though they both knew that wasn’t the truth.

They talked some more. Brielle told him how much she appreciated his kindness. Jeter said it was nothing, that he was happy they got to meet and stay friends. They talked about her Hodgkins’, and how it had returned. Jeter says you never quite know what to say someone in such a situation, so you just try to be yourself, be affirming.

He looked straight at her.

“You’ve got to stay positive,” he said. “You shouldn’t worry about statistics or what anybody says. You are going to beat this. Everything is going to be great.”

They hugged again, and Derek Jeter went off to play the 2,674th game of his career.

“That’s my latest inspiration for pushing through cancer — a hug from Derek Jeter,” Saracini says. She pauses and laughs.

“Not a lot of people get that.”

Brielle Saracini spent most of August in the hospital, getting two blood transfusions, and then a stem-cell transplant, the hope being that it will help her fight the Hodgkins’ off. As much as she wants to be at Derek Jeter Day, she knows she is too weak.

The Yankee shortstop will understand.

“Any time someone is faced with adversity and they approach it the way that she has, in a positive way, that’s inspiring,” Jeter says. “When you’re in a situation like that, a lot of times people take the ‘Why me?’ approach and feel sorry for themselves. She didn’t have that.”

He talked again about Brielle’s strength of character, her determination to make the best of things, no matter that this is a world with terrible people and terrible diseases.

If she keeps getting stronger, Brielle Saracini’s dream is to make it to Fenway Park, the place where, barring a Yankee postseason run, the storied career of Derek Sanderson Jeter will end.

What could be better than seeing Derek Jeter play baseball one more time? To celebrate his goodness, and his consistency? Nobody needs to remind Brielle Saracini that Fenway is just a few miles from Logan Airport, where her father made his last takeoff at 8:14 a.m. on September 11, 2001, having no idea of the evil that had boarded United Flight 175.

No reminders are necessary at all.

That will be there always, but so will her Yankee hat, her Derek Jeter glove, her insistence on doing what Derek Jeter would do, and has long done, seeking light instead of dark.

“I don’t know how I can ever thank him for all things he has done for me over the years,” Brielle Saracini says.