Mike Kelly The Record

His grave lies just inside the cemetery gates, a few feet from a chain-link fence and the rattle and swoosh of cars, trucks and buses on Totowa’s Union Boulevard.

If you go there, you can understand on some level why many people want the Rev. Mychal Judge to be canonized as a Roman Catholic saint.

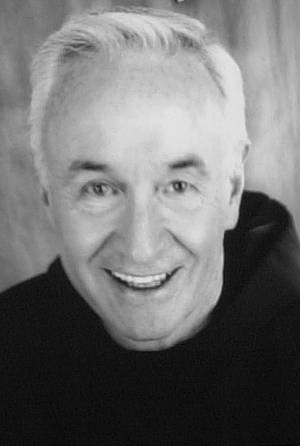

This is an undated photo of the Rev. Mychal Judge, a New York City Fire Department chaplain, who died in the attack on the World Trade Center Tuesday, September 11, 2001. AP file photo

Judge, a Franciscan priest known for his infectious smile and eloquent preaching, served in parishes in Bergen and Passaic counties before moving to Manhattan in the 1990s and becoming a chaplain for the New York City Fire Department. He was killed in the collapse of the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers on September 11, 2001 – officially listed by the city’s medical examiner as the first casualty among the nearly 3,000 people who died that day.

Judge’s grave, amid the final resting places of more than 280 other Franciscan priests at Totowa’s Holy Sepulchre Cemetery, has since become an informal pilgrimage site, with many visitors leaving behind keepsakes – statues of firefighters, prayer cards, rosary beads and even personal notes to “Saint Mychal.”

“If you were here for September 11, you totally get the connection and how much he meant to people,” said Holy Sepulchre’s manager, Mirian Tanis. “He does receive a lot of love even though he is not with us.”

But can love and attention turn Mychal Judge into a saint? And would it matter that Judge was also a recovering alcoholic who reportedly told several close associates that he was gay but never acted on his homosexuality because of his priestly vow of celibacy?

Whether Judge will be officially considered for sainthood may not be decided for decades, if ever, say experts familiar with Catholicism’s scrupulous and often politically and theologically fractious process of naming saints. But Pope Francis’ visit to New York City in September, which includes an interfaith prayer service at the National September 11 Memorial and Museum, has prompted some advocates to push harder for Judge’s sainthood.

It is a campaign that has the support of three seemingly disparate groups – gay rights activists, recovering alcoholics and firefighters, including those who survived the 9/11 attacks as well as others from New Jersey and across America who see Judge as an inspiration.

It is also a campaign that has been bolstered by reports that praying to Judge has resulted in several healing miracles among his followers, including a Rhode Island boy who regained his speech and a Colorado boy whose heart was healed.

Catholic authorities generally require evidence of at least two miracles for a person to be considered for sainthood. But miracles alone are not enough. And those attributed to Judge have not been officially validated by the Vatican.

Judge’s supporters acknowledge that his alleged sexual identity and avowed alcoholism are likely to become fodder for debate and potential controversy. But at the center of the campaign for Judge’s sainthood – indeed, the emotional fuel that energizes many of his supporters who believe he should be canonized – is the story of how he died.

Rushed downtown

On the morning of September 11, 2001, Judge — who was known as “Michael” in North Jersey but later changed his name to the Gaelic form, “Mychal” — left the Franciscan friary on West 31st Street and rushed with firefighters to lower Manhattan when he heard that two hijacked commercial jetliners had crashed into the World Trade Center.

Wearing his white Fire Department helmet and a black FDNY firefighting coat, Judge walked into the lobby of the north tower with scores of other firefighters as debris and bodies fell from above. Soon, it became apparent that he and the other firefighters had placed themselves in a perilous spot.

Video footage from inside the north tower lobby shows him with a deeply worried expression on his face and appearing to be praying for the beleaguered firefighters rushing by him, and for the victims who were jumping or falling to their deaths from the upper floors.

When the neighboring south tower collapsed, debris struck Judge in the head and killed him, the medical examiner said. Authorities now say he was not kneeling and administering the last rites to a dead firefighter when he was killed, as early news stories reported.

Later, a widely circulated news photograph of dust-covered and grief-stricken rescue workers carrying Judge’s slumped and lifeless body from the smoke and rubble was touted as a modern-day, real life version of Michelangelo’s famous sculpture “The Pietà,” which depicts Mary holding Jesus’ body in her lap after the crucifixion. The rescue workers carried Judge’s body several blocks to St. Peter’s Catholic Church and laid him on the white marble floor in front of the altar.

It wasn’t long before Judge was being touted as a saint — not merely for his widely respected chaplaincy to firefighters, his street ministry to the homeless, and his care for fellow recovering alcoholics and to HIV patients in New York’s gay community, but also for his personal bravery during the 9/11 attacks.

A website was created to promote his canonization. Several biographies were published, including “The Book of Mychal: The Surprising Life and Heroic Death of Mychal Judge” and “Father Mychal Judge: An Authentic American Hero.” Ian McKellen, the acclaimed actor, narrated a documentary film titled “Saint of 9/11: The True Story of Mychal Judge.”

As if that were not enough, Judge’s death also resurrected stories of how he had ministered to a wide variety of North Jersey residents in the 1970s and 1980s in parishes in East Rutherford, Rochelle Park and West Milford – including his intervention in 1974 in a hostage standoff between police and a gunman in Carlstadt. In that incident, Judge climbed a ladder to speak to the man through a second-floor window of a house, and eventually talked him into surrendering to police.

Started with a letter

The official campaign to canonize Judge began with a letter in November 2001 to Catholic authorities from an FDNY captain, John Dunne, who singled out Judge for his heroism and holiness. He received a brief reply that his request would be considered. But there was no follow-up.

Dunne, now 63 and a battalion chief in Greenwich Village, calls Judge “the most spiritual person I’ve ever met in my life.”

“When you were in his presence, you could feel it,” Dunne said. “He has this aura about him.”

Dunne didn’t know it when he wrote his letter in November 2001, but Judge’s sainthood was also being promoted by a prominent New York gay Catholic activist, Brendan Fay.

Fay added a note of controversy to the campaign. He said that Judge, while still a celibate priest, had nevertheless acknowledged to him that he was gay.

Several fellow Franciscan priests who knew Judge well say they never heard him speak about his sexual identity, and that he certainly never told them that he was gay.

“That whole issue did not come up until after he died,” said the Rev. Michael Duffy, who now runs a soup kitchen in Philadelphia but served with Judge in New Jersey and eulogized him at his funeral.

“It was a shock and a surprise to everybody,” Duffy said, adding that Judge never spoke openly about his sexual identity to fellow Franciscans.

To others, however, reports of Judge’s homosexuality were not a shock at all. Besides Fay, former New York Fire Commissioner Thomas Von Essen said he knew that Judge was gay.

Now, 14 years after his death, a question remains: Does Judge’s sexual identity matter one way or the other in the campaign to make him a saint?

“Our world needs people who remind us of our capacity to care and to be loving and to work for peace,” Fay said. “We need stories of hope. And that’s what Mychal Judge most certainly was.”

“Mychal Judge had a way — it was almost instinctive — of relating to people and connecting, whether it was a homeless person or someone in a parish,” said the Rev. Ron Pecci, a Franciscan priest who knew Judge and grew up in Cresskill. “He had an ability to say the right thing at the right time. He touched people.”

Shifting attitudes

In perhaps a small sign that official Roman Catholic attitudes toward gays and other traditionally marginalized groups may be shifting, the chief spokesman for the New York Archdiocese, Joseph Zwilling, pointed out in an interview that Judge’s alleged homosexuality or alcoholism would not necessarily disqualify him from becoming a saint.

“The fact that he was a recovering alcoholic and the fact that he identified as a homosexual, even though to the best of my knowledge he never betrayed his celibacy vows, I don’t think those would be impediment,” Zwilling said. “Being homosexual is not a sin. Being sexually active outside of a marriage between a man and a woman is sinful.”

Still, Zwilling said the archdiocese currently has no official plan to promote sainthood for Judge.

Judge’s priestly order, the Franciscans, while noting that they deeply admire Judge’s work, have adopted a similar position, in part because it goes against their tradition of a life of humility and anonymous good deeds.

“Mychal Judge would have considered sainthood a demotion,” said the Rev. Chris Keenan, a Franciscan priest who grew up in Wood-Ridge and took Judge’s place as an FDNY chaplain after his death.

“It’s really not a proper path for Mychal, certainly not with 3,000 people that day who experienced the same thing he did,” Keenan said. “He would be the first to say that if you’re going to canonize me among the 3,000, that’s fine. But don’t single me out.”

That may be true. But it has not stopped the many admirers who continue to honor Judge.

In June, several hundred people converged on a previously unused pocket park at the corner of Hoboken Road and Paterson Avenue in East Rutherford to cheer the unveiling of a bronze statue of Mychal Judge.

After the speeches, the ceremony ended with a song that organizers of the event said Judge would surly have loved. They sang “Let There Be Peace on Earth.”