John Cichowski The Record

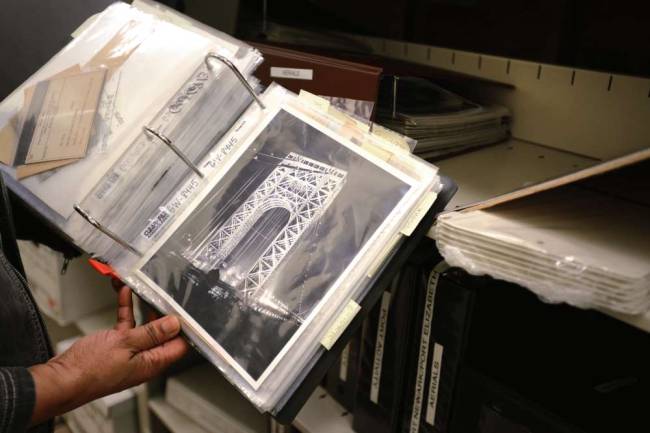

Visit the office of Fort Lee’s top elected official and you can’t help but notice the iconic, black-and-white picture shot long ago by a photographer for the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

“It’s our symbol,” Mayor Mark Sokolich said of the photo of the George Washington Bridge, taken prior to the traffic jams that would eventually clog the tiny borough’s streets.

Only a small amount of the Port Authority’s archival material survived the 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. Photo by Carmine Galasso

Like a honeymoon picture, it symbolizes the bliss preceding the strain of the long haul. By 1991, Sokolich’s predecessor — Jack Alter, who has since died — wasn’t sure what would happen when he asked the Port Authority for bridge photos for his office. But like a husband bearing flowers after a spat, the agency sent him several images for copying.

It turned out that such generosity was routine, but it stopped abruptly after the horror of September 11, 2001.

“When the World Trade Center fell, we lost almost everything,” said John Denise, a Port Authority marketing supervisor.

Nearly all the historic photos taken since 1922 were gone: original pictures of construction teams completing the Holland Tunnel. Shots of the Pan Am Clipper at La Guardia Airport. Technical photos showing the engineering intricacies of billions of dollars of bridge, tunnel and airport projects over the decades.

“Promotional stuff, too, like Broadway shows — all gone,” said Denise. “There also was film we shot showing projects under construction. And the cataloging that listed everything — gone. Basically, we lost our library.”

Lost. Gone. But, in many cases, replaceable.

For example, shortly after the Twin Towers fell, Alter returned an old favor by sending the Port Authority photographic copies of the copies he had been given in 1991.

“When you give a part of yourself,” he explained in a 2006 speech, “it can come back to you in unexpected ways.”

Calls were placed to historians and others who, like Alter, had been given similar copies. Denise and his assistant, Cynthia Armour, didn’t keep track of these donors, but they said historians, documentary filmmakers, universities and engineering firms all responded.

And finally, in 2002, Ground Zero itself yielded the biggest trove.

“I got a call saying firemen had pulled some cabinets up from B-3,” he said, referring to the third basement level of Tower 1 where most of the records were stored.

But time was short. The file cabinets were covered with asbestos, so the main priority was cleaning the area within a reasonable time. Wearing protective gear, Denise and a co-worker began sorting through the cabinets almost as fast as grappling hooks lifted them out of the ground.

“We kept loading files into plastic bags,” he recalled. “We worked 24 hours straight.”

There was no time to sort effectively. The best they could do was gently fill bag after bag with film, videos and pictures.

“Because of the asbestos, the cabinets all had to be destroyed and the bags had to be disposed of properly,” Denise recalled. “Each picture, each file was sent to an outside contractor for cleaning.”

Library disbanded

There wasn’t time to save everything. Luckily, though, additional photos were found in storage locations at Kennedy International Airport and elsewhere.

“But compared to what we had, it was only a small portion,” Armour said. “The color photos, for example, are mostly faded. The black-and-whites are much sharper.”

Denise and Armour couldn’t accurately quantify the loss. The job of digitally scanning all the photos and producing a database that accurately tabulates every item has proved tedious, too. Finishing these tasks may take years. A fully staffed library, which was disbanded after the 9/11 attack, has not been restored, they said.

If you’re not an engineer or a history buff, these losses might sound trivial, especially when weighed against nearly 3,000 deaths, thousands of injuries and health conditions, and the destruction of both main towers and several other buildings. Denise and Steve Coleman, the agency’s chief spokesman, noted that preserving Port Authority artifacts took a back seat to much more important priorities in the years after the attack.

But they also cited the importance of maintaining a graphic record of the Port Authority’s impact on the growth of the region in the 20th century. The images remain a proud reminder of an age before hard hats, when strong men wielding hammers and rivets teamed with big dreamers to forge lasting landmarks such as the George Washington Bridge, the Holland Tunnel, the Lincoln Tunnel and three major international airports that spurred comparable projects throughout the nation and the world.

“The pictures we have here,” said Armour, “bring it all to life.”

Access to them was long ago restored. Like the big, black-and-white photo in the Fort Lee mayor’s office, many of the more common photos remain available on demand for reprinting. Requests keep coming in, said Coleman.

Over the past three years, he estimated that 75 permission requests have been made to use Port Authority photographs in films, books and magazines through the tab on the agency’s “Contact the Archive” request form at portauthorityarchive.com/contact. In addition, dozens of requests are made by the general public.

At the same time, the agency continues to solicit additional artifacts that remain lost following the 9/11 attack.

“If the Port Authority needs more of our pictures,” said Sokolich, “tell them we’re more than happy to oblige.”