By Michael Daly Daily Beast

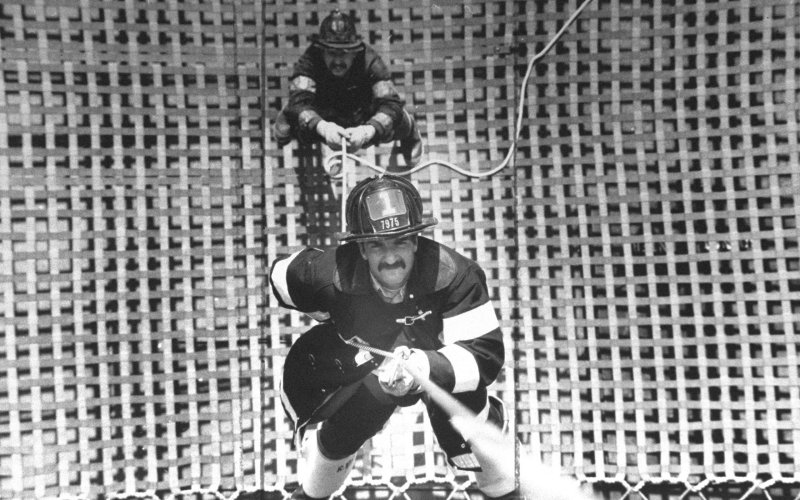

Ron Bucca – New York Daily News Archive via Getty

He defied death and gravity to selflessly protect New Yorkers until his final moments in the Twin Towers. Why Ronald Bucca’s legacy still reverberates—even at the hardest core of ISIS. Two former commanders of the detention camp that once held the future leader of ISIS are expected to attend this year’s 9/11 memorial for the fallen FDNY firefighter for whom Camp Bucca was named.

No doubt they keenly feel the frustration of having once held Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi prisoner only to see him freed to prove himself the very worst of the bad guys. As al-Baghdadi was released, he jokingly told one of these commanders that he would see him in New York.

What the commanders will in fact encounter in New York is the legacy of Firefighter [sic Fire Marshal] Ronald Bucca.

And in attending Thursday’s annual memorial in downtown Manhattan for Bucca and the other members of his FDNY battalion who perished at the World Trade Center, the commanders will be reminded of one of the most remarkable of the good guys.

For all of us, the story of Ronald Bucca offers everything we need to prevail in this unrelentingly dangerous world: dedication and resilience and determination and courage and selflessness.

He enlisted in the Army at age 17 toward the end of the Vietnam War and continued to serve with the reserve special forces after he joined the FDNY. He was a firefighter with the elite Rescue 1 squad when he attempted to assist an FNDY lieutenant at a blaze on the Upper West Side of Manhattan and fell five floors.

Fire officials afterward noted that Bucca had struck a telephone wire and a pair of cables on the way down, but speculated that his survival may have ultimately been due to his special forces parachute training. He landed on his hands and feet like some huge, muscular cat.

“He’s lucky, lucky, lucky,” his wife, Eve Bucca, noted. “He used a lifespan of luck.”

New York’s then-mayor, Ed Koch, rushed to Bellevue Hospital and stood amazed.

“He’s the first man I’ve ever met who I can say has learned how to fly,” Koch said.

As he recovered from a broken back and the rest of his injuries, Bucca learned the other patients included someone else whose survival had been declared a miracle—a police officer who had been shot in the throat and paralyzed. Bucca ignored what must have been excruciating pain as he made his way to the bedside of Police Officer Steven McDonald.

“How you doin’?” Bucca asked.

McDonald was still physically unable to speak.

“I couldn’t communicate because of the gunshot wounds, but that didn’t matter to him,” McDonald would later recall. “He knew I was in a deep depression, dark moods, and he would spend time with me, trying to give me pep talks.”

Bucca returned to see McDonald day after day.

“I just remember him in his hospital pajamas and a back brace, and he would always come in and see if I was OK, if I needed anything,” McDonald would say. “He had been through a very bad time himself, but he always took the time to check on me.”

McDonald’s wife, Patti Ann, took to calling Bucca “the Flying Fireman.”

Bucca could have retired at age 32 with a tax-free disability pension. But that very first day at the hospital he had made a pledge to his wife.

“I’m going back to Rescue 1 in a year!”

He was determined to resume saving lives and he dismissed the experts who predicted he would never be fit for full duty. He pushed himself through long months of agonizing physical therapy,

“I designed my own rehabilitation program—calisthenics, running and other exercises,” Bucca was quoted saying. “There was never any doubt in my mind.”

In September 1987, Bucca did indeed return to Rescue 1’s firehouse on West 43rd Street. He became a fire marshal in 1992 and was at the scene after the World Trade Center was bombed the following year.

Bucca subsequently became the sole FDNY member of the Joint Terrorism Task Force. He also remained an Army Reservist, serving as a Green Beret with the 11th Special Forces Group and the Defense Intelligence Agency. He was a firefighter-soldier who was among the first of any agency to warn about the danger of al Qaeda.

At the arrival of the new millennium, the nation went on high alert for a big New Year’s Eve attack. The moment passed without event and our leaders seemed to imagine that the danger passed with it. The FDNY spot on the JTTF was among the items deemed no longer worth the expense in a time of budget cuts.

From what he had learned on the JTTF and continued to see with military intelligence, Bucca was certain the threat was only growing. He kept a set of building plans of the Twin Towers in his fire marshal’s locker.

On the sunny morning of September 11, 2001, Eve Bucca was at her own job as a nurse at a Westchester hospital. Her husband telephoned.

“A plane just went into the Trade Center, and we’re going into the building now,” he told her.

The attack he expected had come and the building he spoke of was the South Tower of the World Trade Center. Bucca hung up the phone and started up the stairway with fellow fire marshal John Devery. The other marshal stopped to assist a woman who had blood streaming down her side. Bucca kept on and became the only firefighter that day to climb all the way to the Sky Lobby on the 78th floor.

Up in the tower, Bucca was joined by Battalion Chief Orio Palmer, who had managed to get a freight elevator to bring him part way. They began assisting whomever they could and made plans to fight this blaze on high.

“We’ve got two isolated pockets of fire,” Palmer radioed at 9:52 a.m. “We should be able to knock it down with two lines.”

Palmer used radio code to report that many of the civilian victims were beyond saving.

“78th floor, numerous 10-45s, Code One,” he said.

A civilian named Richard Gabrielle was trapped under a pile of marble, but alive during those last minutes. His wife would later be quoted expressing gratitude for the presence of those most determined of firefighters.

“The fact that Rich, still alive, was not alone—at least he knew there was help, and thought that they were getting out,” Monica Gabrielle said.

At 9:58:59 a.m., the South Tower collapsed. Bucca must have placed his turnout coat protectively around several civilians, for it was later found still wrapped around them. His remains were recovered on Oct. 23, 2001. He was 47 and he had served his country and his city for three decades.

The many who attended Bucca’s funeral included Steven McDonald. The two had stayed [in] touch over the years, and Bucca kept a picture of McDonald in his home. McDonald kept the image in his heart of Bucca at his hospital bedside.

“We always talked about getting together,” McDonald later said. “And then he was gone.”

Bucca’s wife delivered a eulogy.

“I choose to be grateful for the time I had with him,” she told the mourners. “I know some bonds can never be broken… He saved lives and he touched lives.”

His son, Ronald Bucca, Jr., also spoke.

“My father never bragged or talked about his accomplishments, but the family knew what he did,” the son said.

The son walked alongside the fire rig that bore the flag-covered coffin. And in the days ahead he followed his father into the Army special forces. The son’s hope was to get the guys behind the murder of his father and so many others.

But when Osama bin Laden was finally killed, the son found himself in Iraq, and it was not his first deployment. The son paid more than one visit to Camp Bucca, not imagining that the prisoners who passed through this place named after his father included a man who would go on to head an organization too bloodthirsty even for Al Qaeda.

On the eve of the 13th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, President Obama was to address the nation about his plans to take on ISIS. Young Ronald Bucca and his mother were at a gathering place in downtown Manhattan, making preparations for the next day’s memorial. The guests this year were expected to include two men who commanded Camp Bucca before it was shut and its prisoners freed, including al-Baghdadi.

With the Bucca son and the Bucca widow was the spirit of the Flying Fireman, the firefighter-solider who embodied all we need to prevail against any enemy.

The bad guys may have Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, but we have the example of Ronald Bucca.

“My dad,” his son said.

The son sees it as one long story, from the 1993 bombing to 9/11 to the opening of Camp Bucca to the closing of Camp Bucca to the continuing conflict in Afghanistan to the intensifying conflict with ISIS.

“I just hope we come together to prevent another 9/11,” he said. “And prevent more sons from losing their dads.”