By David Abel Boston Globe

The Stony Creek granite used in the memorial was supposed to last between 50 and 100 years. Essdras M Suarez/ Globe

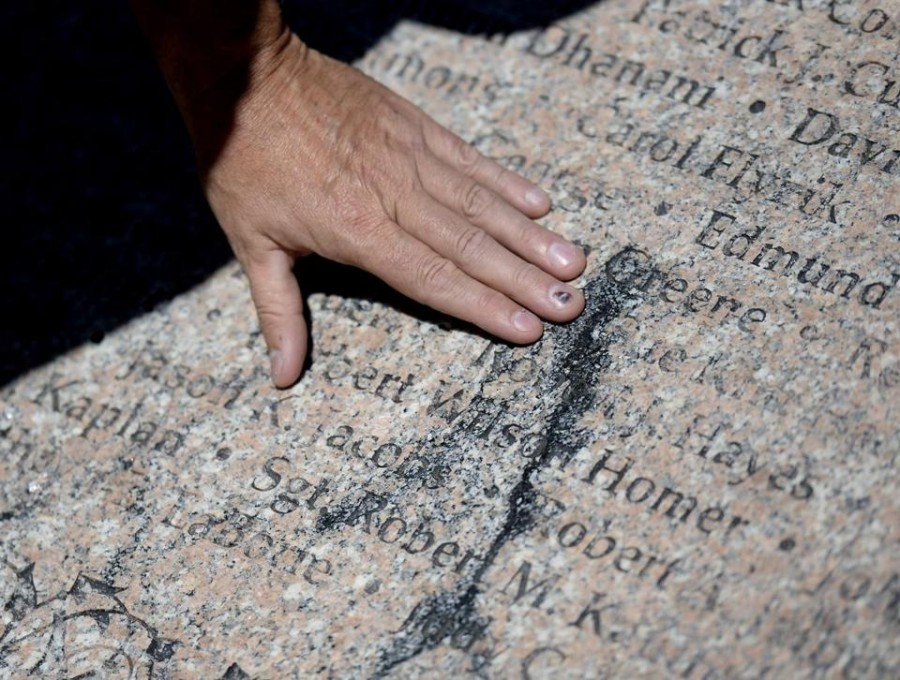

Long black veins scar the pink granite, blotting names meant to be etched in perpetuity. The smooth edges are scuffed from a steady battering by skateboarders, and the mortar between the large stone blocks is crumbling.

From the surrounding benches, it’s unclear what the Garden of Remembrance seeks to summon, as the lettering and names are fading into obscurity. The inscription at the center — September 11, 2001 — is only legible from a few inches away.

A decade after officials inaugurated it in a quiet corner of the Boston Public Garden, the muted memorial to the 206 people with ties to Massachusetts who died in the terrorist attacks appears to be deteriorating.

“It’s heartbreaking, like the names are being washed away,” said Keith Graveline, 53, of Easton, while trying to decipher the inscribed names on a recent afternoon. “This is a memorial that should be maintained.”

The Stony Creek granite, which came from a Connecticut quarry, was supposed to last between 50 and 100 years, but officials from the Massachusetts 9/11 Fund, which oversaw the creation of the memorial and endows its upkeep, fear it may have to be replaced much sooner.

“Our maintenance plan has to be reevaluated,” said John Curtis, vice president of the fund’s board. “Some of our expectations haven’t been met.”

Complaints about the stone — how its natural striations make the names hard to read — came in to city officials soon after the memorial was unveiled in 2004. But the fading luster, the apparent need for new sealant, the vanishing of the lithichrome paint in the etchings, and what appear to be widening and darkening veins in the granite are new causes for concern.

A memorial to the 206 people with ties to Massachusetts who died in the 9/11 terror attacks appears to be deteriorating. Essdras M Suarez/ Globe

On a recent visit to inspect the memorial, a tranquil nook near the park’s Newbury Street entrance that includes five granite blocks shaded by apple and dogwood trees, Chris Cook, the interim commissioner of the city’s Parks and Recreation Department, noted the problems. He said the city would use some of the memorial’s privately raised $350,000 endowment to reapply the seal and improve the etching, which he expects to be done after the winter.

Some upkeep — such as pruning the surrounding holly bushes and restaining the faded benches around the memorial— is expected to occur before next week’s anniversary of the attacks. Cook expressed surprise at how the granite has fared during the decade and said he would meet with representatives of the 9/11 fund about whether it should be replaced.

“I think the reapplication of the lettering will dramatically change how it appears,” he said, “But we can’t ignore the long-term deterioration concerns.”

To dissuade skateboarders from riding the upper edge of the memorial, the city added an unobtrusive chain-link fence between the bushes and the granite. Cook said it seems to be working, though many streaks and scuff marks remain on the lower edge.

Mayor Martin J. Walsh, concerned about the memorial after recent visits, said he would make sure the city does a better job maintaining it. “If a better quality stone is needed, we’ll do it,” he said in a phone interview. “I have no doubt.”

Jamie Crothers, who oversees sales in New England for Granicor Inc., the Canadian company that provided the granite for the memorial, estimated that replacing the stone would cost about $40,000. There would be no refund: Crothers said the stone itself was not defective. But as he inspected the memorial on a visit last week, he said he was surprised the designer chose Stony Creek granite, which he said is known to make inscriptions hard to read.

“That piece of stone should have never been selected for engraving,” he said of one granite block splotched with dark veins obscuring more than a dozen names. “There’s nothing wrong with the integrity of the stone; it’s typical of this kind of granite. But it’s not something I would have recommended to use for this.”

Victor Walker, a landscape architect who conceived and designed the memorial, said he and victims’ relatives chose Stony Creek granite because it was used for other monuments and fountains in the Public Garden.

Walker wondered if repeated pressure washing by city workers was taking a toll on the sheen and making the dark veins appear to be more pronounced. But he would not second-guess the stone’s selection.

“I believe the process and stone selection was very appropriate,” he said.

Ed Larson, executive director of the Barre Granite Association, a trade group for Vermont manufacturers, called moisture “the biggest enemy” to granite. Rain, cleaning agents, and other elements could break down the feldspar and make other minerals in the dark veins more prominent.

“It will probably get more pronounced over time,” he said. “The granite could turn all black.”

But officials from Stony Creek Quarry Corp. said no one should be surprised by the motley coloring of their granite, which has been used on the façade of South Station and the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty.

“This is perfectly characteristic of Stony Creek granite,” said Darrell Petit, business development director of the Connecticut company, after reviewing pictures of the Boston 9/11 memorial. “From my perspective, the poetry is greater and enhanced when Stony Creek is there in all its glory, showing its variegation. I think it hints at the horror of what happened.”

Elizabeth Vizza, executive director of the Friends of the Public Garden, said having the inscriptions blend in with the stone echoes the memorial’s minimalist design.

“This is a healing, meditation space, which wants to be a quiet retreat,” she said. “But you shouldn’t have to work hard to read the names. That’s a distraction.”

On a recent afternoon, a number of visitors had to get close to see what the memorial was commemorating.

“I had no idea this was for September 11,” said Dina Mareen, 33, a tourist from Germany who was sitting on a bench beside the memorial. “It’s kind of ridiculous. You can’t read it, even from here.”

Bruno Maccione, 50, of New York City, worried that the memorial’s condition was symbolic.

“It’s too easy to overlook,” he said. “I hope this doesn’t mean our memory of that day is fading.”