By David W. Dunlap The New York Times

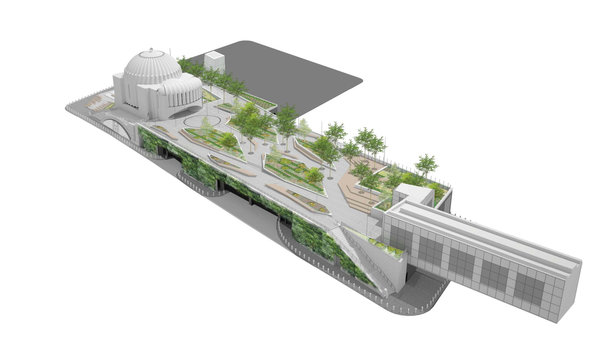

A rendering of the proposed plan for Liberty Park, immediately south of the National September 11 Memorial, to be built on the rooftop of the entrance to the vehicle security center. Some features may change during construction. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

The World Trade Center’s best-kept secret has finally come to light.

It is an elevated park, slightly larger than an acre and 25 feet above Liberty Street, that will command a panoramic view of the National September 11 Memorial when it opens to the public, probably in 2015. Liberty Park, as it is called, is meant to offer a pleasant and accessible east-west crossing between the financial district and Battery Park City; to create a landscaped forecourt for the new St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church; to provide a gathering space for as many as 750 people at a time; to allow visitors to contemplate the whole memorial in a single sweeping glance from treetop level; and to serve as the roof of the trade center’s vehicle security center. For the moment, the park is an empty concrete expanse. The pedestrian bridge over West Street that will connect it to Battery Park City — the bridge that survived the September 11 attack — currently falls several yards short of its future landing spot.

While the general outlines of the park have been known for years, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey has been sparing in its public discussion of the project, in part because not every detail of its design and construction has been settled.

But the Port Authority’s hand was forced somewhat last month when sumptuous images of St. Nicholas Church and Liberty Park appeared on the website of the architect Santiago Calatrava, who is designing the church. The park was rendered in sufficient detail that it was possible for the first time to understand its basic design.

The renderings, at least those shown in The TriBeCa Citizen, included what authority officials said were outdated features. For instance, “Sphere,” commissioned for the original World Trade Center, was shown just outside the church entrance. The authority’s executive director, Patrick J. Foye, said in 2012 that he favored placing “Sphere” on the memorial plaza, but there has been no movement since then to relocate it.

However, the renderings were accurate enough that the authority opened up a bit last week and elaborated on the park. The principal designer is Joseph E. Brown, a landscape architect who is the chief innovation officer at Aecom, an architectural, engineering and construction consultancy with headquarters in Los Angeles.

Mr. Brown faced many challenges. This could not be a street-level park, since it was to sit atop a bulkhead with doors tall enough to accommodate large trucks and tourist buses. The park had to complement the memorial without overwhelming it or imitating it.

Its most unusual feature will be a “living wall” along the Liberty Street facade — essentially a vertical landscape, roughly 300 feet long and more than 20 feet high, made of periwinkle, Japanese spurge, winter creeper, sedge and Baltic ivy. (Another example of this kind of planting are the “vertical gardens” of the David Rubenstein Atrium at Lincoln Center.)

Walkways from the pedestrian bridge will meander among islands of plantings to stairways at three corners of the bulkhead. There will also be a fairly straight inclined path down to Greenwich Street, for greater accessibility.

To take advantage of the views, Mr. Brown designed a continuous overlook along much of Liberty Street, as well as a gently curving balcony near the base of the church.

A monumental staircase paralleling Greenwich Street, directly behind the church, is intended to be as inviting as the steps of the Metropolitan Museum on Fifth Avenue — perhaps even more so, since there will be wood benches on the seating tiers. There will also be a small amphitheaterlike elevated space at the opposite end of the park.

About 40 trees and shrubs will be planted: honey locust, stellar pink dogwood, apple serviceberry and two varieties of witch hazel: Arnold Promise and Pallida. Quite deliberately, there will not be swamp white oaks, the trees used on the memorial plaza. Plantings have been chosen to present a variety of colors through the seasons.

Some details, including features shown in renderings released by the Port Authority, may change after construction bid proposals are received. Contractors may propose changes in plant types, for instance. Authority officials expect that progress will be visible on the park’s contours by early next year. They estimated that the park will cost $50 million.

Catherine McVay Hughes, the chairwoman of Community Board 1 in Lower Manhattan, was among the neighborhood leaders who were given a tour of the park space recently.

“They have taken what could have been a barren rooftop and turned it into much needed public space for the community,” Ms. Hughes said.

“Because it’s elevated, it’s out of the flow of the street,” she added. “There’ll be a sense of calm.”

And the emotionally wrought yet relentlessly busy trade center site needs all the calm it can claim.