By David W. Dunlap New York Times

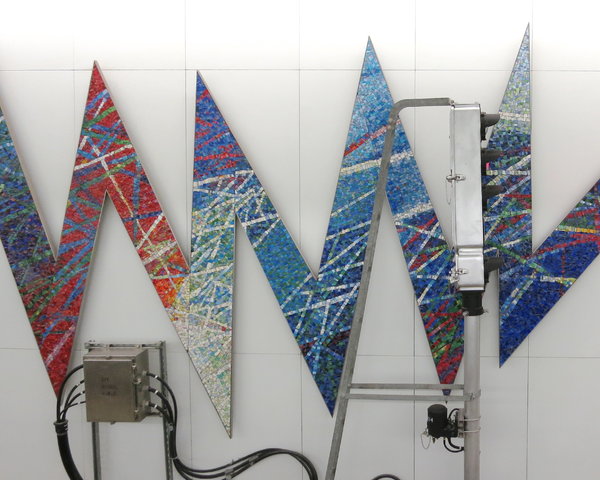

Platform A at the World Trade Center Transportation Hub. In front is “Iridescent Lighting,” from Friuli-Venezia Giulia in Italy. Credit Ozier Muhammad/The New York Times

How can a $3.94 billion building be made to look cheap?

Clunky fixtures and some rough workmanship in the underground mezzanine of the World Trade Center Transportation Hub, a small part of which opened last week, detract from what is meant to be breathtaking grandeur.

Ten years ago, the architect Santiago Calatrava and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey seduced a large audience, this reporter included, with a vision of a dazzling new PATH train station rising at the trade center site. Where ground zero was dark, misshapen, jagged and sorrowful, the transit hub was to be brilliant, smooth, pristine and promising.

That vision may yet materialize. Some flaws that are now visible can and probably will be fixed. And when the station fully opens in 2015, the whole of it may be so spectacular that little shortcomings are easy to overlook.

“We will deliver to New York a great space,” Mr. Calatrava said this week.

It is hard not to notice the loose threads, however, since Port Authority executives and state officials have boldly invoked Grand Central Terminal as the model for the trade center hub. Grand Central owes its enduring appeal both to monumental spaces and to an abundance of meticulously crafted detail.

“I believe that God is in the details,” Mr. Calatrava said, borrowing an aphorism from Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. “But we’re not working here on a Seagram Building.”

He distanced himself somewhat from the entirety of the hub project, noting that his office was a subcontractor to the Downtown Design Partnership, a joint venture of STV and Aecom, two architectural and engineering giants. He said he was a 20 percent participant in this triumvirate.

“I’m not excusing myself,” he said. “This is a fact.”

Mr. Calatrava and Frank Lorino, a colleague in Santiago Calatrava New York/Festina Lente, said their office was chiefly responsible for the design and engineering of the sinuous steel elements, for the support structure on which the No. 1 subway line will run through the station and for finishes like the marble floors.

“We have fought to bring the highest degree of quality to the project,” Mr. Lorino said, “but the concerns of time, budget and scheduling have often taken precedence over quality.”

A signal was installed in front of the mural, a gift to the city. Credit David W. Dunlap/The New York Times

Some design decisions did not involve Mr. Calatrava’s office at all. For instance, a 118-foot-long mosaic mural, “Iridescent Lightning,” given in 2003 by the regional government of Friuli-Venezia Giulia in Italy, was installed on the wall opposite the new Platform A. After it went up, a train signal was erected directly in front of it.

Other design decisions were imposed by circumstance. Columns and beams that were supposed to have almost a silken finish look more as if they are covered in stucco.

The rough coating is a fireproofing substance known as intumescent epoxy. Mr. Lorino said “considerable time and cost” would be needed to smooth out the coating. “The client was not prepared to spend that additional money,” he said. “In the end, it is more important that the finish be consistent than perfectly smooth.”

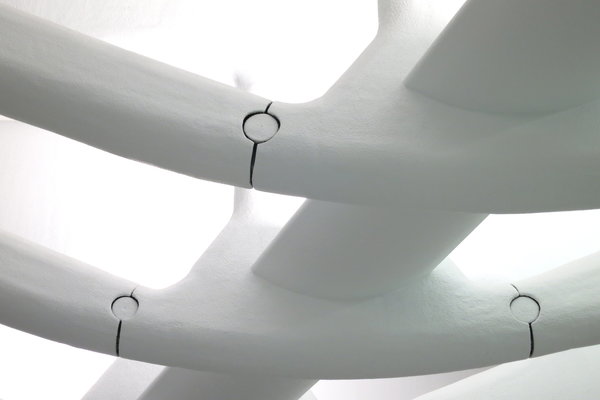

Among the details that are just a bit off are the joints in the steel beams, left conspicuously unfinished. Credit David W. Dunlap/The New York Times

That is because the separation of columns and beams is critical. To put it simply, such joints reduce the stress placed on the vertical columns by forces acting on the horizontal beams; in the worst case, those from an explosion.

Mr. Calatrava said that the joints could have been masked, but that he found them “aesthetically correct.” He said he had designed even more prominently articulated joints at the Guillemins Station in Liège, Belgium.

To reduce visible crevices around the joints, Mr. Lorino said, the surface of the pins can be made flush with the surrounding steel. Joints in the nearby east-west concourse have already been adjusted that way and they do look more refined.

What appeared as if it would be a purely sculptural ceiling is punctuated — of necessity — by lighting fixtures, smoke exhaust grilles, sprinkler heads and security cameras. Some of the aluminum ceiling panels are buckling.

The camera housings “were required to be conspicuous by the P.A. so that they act as a deterrent,” Mr. Lorino said, referring to the Port Authority. The buckled panels, he said, were “a product of the lack of quality construction.”

Lighting fixtures are noticeable on many beams as well, where they have been attached to the surface rather than recessed. If such a thing can be imagined, they look like albino garden slugs (less the feelers) nestled in abstract tree limbs.

Caulking will be applied to reduce the contrast between the fixtures and the beams, Mr. Lorino said. But not much more can be done. Had the steel been cut away to create recesses, its load-bearing capacity would have diminished.

The garden slugs, in other words, are going nowhere fast.