David W. Dunlap, New York Times

When the chain-link fences are pushed aside this week, pedestrians will be able to cross the crossroads of Greenwich and Fulton Streets in Lower Manhattan. This is big news.

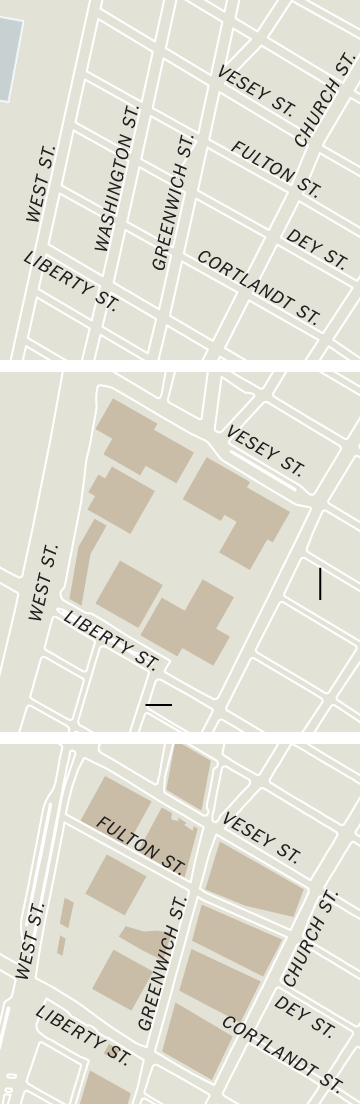

Like eight other intersections, the crossroads was subsumed in 1967 into the 16-acre superblock on which the World Trade Center was built. Since September 11, 2001, its four corners have been occupied by rescue workers, recovery workers or construction workers.

On Thursday, the crossroads is to return to public use for the first time since ham-radio and hi-fi buffs swarmed the little appliance and electronics stores of Radio Row, squeezing past flower and food shops whose goods spilled out to the streets, resisting the temptation to buy a three-and-a-half-foot baby elephant for $3,000 at Trefflich’s animal dealership.

At the crossroads now are the nearly finished and already dazzling Oculus pavilion of Santiago Calatrava’s $3.9 billion transportation hub; a new half-acre of landscaped plaza at the front entrance of the National September 11 Memorial Museum; the full-block site of 2 World Trade Center, newly redesigned by Bjarke Ingels and already being called the “stairway to heaven”; and a parcel set aside for a performing arts center.

The public will be able to reach the crossroads on foot from the north, west and south. For now, the route from the east is blocked by construction activity and staging.

Here is a prediction: the crossroads will instantly provide a popular photo-op foreground for Mr. Calatrava’s zoomorphic Oculus, whether you think the pavilion looks like a stegosaurus lumbering through the swamp white oaks or like a bird taking flight from the treetops — or simply like a Calatrava sculpture on a monumental scale.

“We feel great about opening it to public access,” said Patrick J. Foye, the executive director of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which owns the trade center.

“Just as the twin towers were the products of their time, when the reigning architectural and urban design ethos was superblocks and massive structures,” he continued, “today people want transit-oriented development, access to public transportation, the restoration of streets and the ability of pedestrians to walk up and down.”

For fear of vehicle-borne bombs, however, the crossroads will be closed to traffic.

In the earliest days of the trade center redevelopment, planners urged the authority to recreate as much as possible of the 12-block grid that the original project had eradicated.

But Gov. George E. Pataki pledged in 2002 that no new construction would occur on the “footprints” of the twin towers, effectively ruling out the full restoration of Washington, Cortlandt and Dey Streets.

Greenwich Street, an important north-south route that runs from the Battery to Greenwich Village, was the first to be restored, when the new 7 World Trade Center was squeezed to accommodate at least a visual corridor, if not a through street.

The World Trade Center Transportation Hub, seen from Church Street. CreditHiroko Masuike/The New York Times

And it made enormous sense to recreate Fulton Street, long the most critical east-west thoroughfare in Lower Manhattan, since it runs from the Hudson to the East River — and, importantly, did not bisect the memorial site.

In the end, the authority divided the original World Trade Center superblock into four great parcels around the Greenwich-Fulton crossroads. The importance of the intersection was recognized more than a decade ago by Kevin M. Rampe, then the president of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, who called it the “100 percent corner.”

Though the memorial formally opened in September 2011, the plaza in which the great memorial pools are set was closed to anyone but ticketholders until May 2014, when the underground museum opened. Construction had limited access until now.

“This will open up the entire memorial plaza,” Steven Plate, the director of World Trade Center construction, said on Monday.

Access to the plaza from most directions is regarded as “incredibly exciting” by memorial and museum officials, a spokesman, Michael Frazier, said. The Greenwich-Fulton crossroads “was always considered a primary way to enter the plaza,” he said, and queuing for the museum will eventually take advantage of the additional space that will be available.

Underground, an important north-south pedestrian corridor leading to and from the PATH terminal will open in mid-July, said Erica Dumas, a spokeswoman for the authority.

At street level, a temporary blocklong pedestrian chute will guide pedestrians arriving from Vesey Street, to the north. The southern approach will be along Greenwich Street, which looks like a New York street, with a roadbed, curb stones and anti-terrorist bollards.

Yet on Monday something appeared unfamiliar about the scene along a part of the street that is already open to pedestrians. Glenn P. Guzi, a program director of the Port Authority, identified the anomaly.

People were using the crosswalk, he noted in amazement.

Ah, that was it. New Yorkers hadn’t shown up yet.

Correction: June 24, 2015

An earlier version of a picture caption with this article misstated the view from which The World Trade Center Transportation Hub was taken. It was Church Street, not Greenwich Street.